Leaky Gut and Inflammation: Why You’re Still Feeling Unwell Despite Eating Right

Our gut is often called our second brain, and for good reason. It’s a complex ecosystem teeming with trillions of microorganisms, responsible for digesting food, absorbing nutrients, and acting as a critical barrier against harmful substances. But what happens when this vital barrier becomes compromised? This is where the concept of “leaky gut” comes into play, a term that has gained significant attention in health discussions.

In this article, we will explore what leaky gut is, delve into its potential causes, examine the varied symptoms associated with it, and discuss current approaches to treatment, keeping in mind that while “increased intestinal permeability” is a recognized scientific phenomenon, the term “leaky gut syndrome” is still debated in conventional medicine.

What Exactly is Leaky Gut?

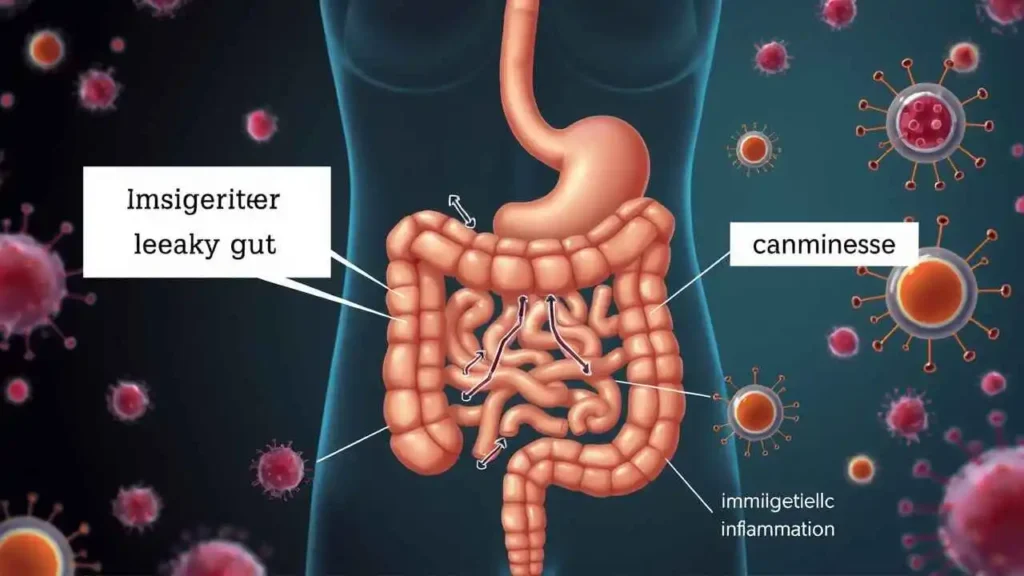

At its core, leaky gut refers to a condition where the lining of the small intestine becomes more permeable than it should be. Think of the intestinal lining as a finely woven mesh or a gatekeeper. In a healthy gut, this lining has tiny holes (called tight junctions) that allow water and essential nutrients to pass through into the bloodstream while blocking the passage of larger, undigested food particles, microbes, and toxins.

When we talk about a “leaky gut,” these tight junctions loosen or break down, allowing these unwanted substances to “leak” through the intestinal wall and enter the bloodstream. The body’s immune system then identifies these foreign invaders and mounts an inflammatory response. Over time, this chronic inflammation can potentially contribute to a range of health issues.

Scientists often refer to this condition as increased intestinal permeability. While the exact mechanisms are still being studied, the breakdown of this barrier is a recognized factor in various diseases, particularly inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and celiac disease. The debate lies in whether increased intestinal permeability is a primary cause of other, less specific conditions, or if it’s a symptom or consequence of those conditions.

Potential Causes of Increased Intestinal Permeability

Several factors can contribute to the weakening of the intestinal barrier. Often, it’s a combination of these elements working together that leads to increased permeability. We can categorize these causes as follows:

- Dietary Factors:

- High Sugar Intake: Excessive consumption of refined sugars and processed foods can feed unhealthy bacteria in the gut and damage the gut lining.

- Low Fiber Intake: Fiber is essential for feeding beneficial gut bacteria, which produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that nourish the gut cells and strengthen the barrier. A lack of fiber starves these beneficial bacteria.

- Consumption of Inflammatory Foods: Foods like gluten, dairy, soy, corn, and artificial additives can trigger inflammation in sensitive individuals, potentially disrupting the gut lining.

- Alcohol Consumption: Chronic or excessive alcohol use can directly damage enterocytes (intestinal cells).

- Medications:

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Medications like ibuprofen and aspirin can damage the gut lining, leading to increased permeability.

- Antibiotics: While necessary for fighting bacterial infections, antibiotics can disrupt the balance of gut bacteria, potentially harming beneficial species that help maintain gut integrity.

- Infections:

- Bacterial Infections: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) or infections from pathogens like E. coli or Salmonella can damage the intestinal lining.

- Fungal Overgrowth: An overgrowth of yeast, particularly Candida, can impair gut barrier function.

- Parasites: Certain parasitic infections can injure the gut wall.

- Chronic Stress: High levels of stress hormones, like cortisol, can negatively impact the gut microbiome and the integrity of the intestinal barrier. The gut-brain connection is bidirectional, meaning stress in the mind can manifest in gut issues.

- Toxins: Exposure to environmental toxins, pesticides, and heavy metals can contribute to gut damage.

- Nutrient Deficiencies: Deficiencies in certain nutrients, such as zinc, glutamine, and vitamins A and D, are important for maintaining the health and structure of the gut lining.

- Dysbiosis: An imbalance between beneficial and harmful bacteria in the gut microbiome is strongly linked to increased intestinal permeability. When pathogenic bacteria outnumber beneficial ones, they can produce toxins that damage the gut lining.

It’s crucial to understand that these factors don’t exist in isolation. A person might have a poor diet, be under chronic stress, and have recently taken a course of antibiotics, creating a perfect storm for developing increased intestinal permeability.

Potential Symptoms Associated with Leaky Gut

Because the gut is connected to so many systems in the body (immune, nervous, endocrine), the symptoms potentially linked to increased intestinal permeability can be wide-ranging and often non-specific. This is part of why it’s challenging to diagnose as a standalone syndrome. However, many people who address known causes of increased intestinal permeability report improvements in the following areas:

- Digestive Issues:

- Bloating and gas

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Chronic diarrhea or constipation

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) symptoms

- Systemic Symptoms:

- Chronic fatigue or low energy

- Joint pain

- Skin problems (e.g., eczema, acne, psoriasis)

- Headaches or migraines

- Brain fog, difficulty concentrating, memory problems

- Mood issues (anxiety, depression)

- Food sensitivities or intolerances (new onset or worsening)

- Nutrient deficiencies due to poor absorption

It’s important to reiterate that these symptoms can be caused by many other conditions. Therefore, experiencing one or more of these symptoms does not automatically mean you have a “leaky gut syndrome.” However, if we experience several of these symptoms, especially alongside known risk factors, it’s a good idea to investigate gut health as a potential contributing factor.

Diagnosing Increased Intestinal Permeability

While there isn’t one widely accepted clinical test for “leaky gut syndrome” in conventional medicine, scientists and some functional medicine practitioners use tests to assess intestinal permeability. One common test is the lactulose/mannitol test.

- We drink a solution containing two non-digestible sugars: lactulose and mannitol.

- Mannitol is a small molecule that passes easily through a healthy gut lining.

- Lactulose is a larger molecule that should only pass through the tight junctions minimally in a healthy gut.

- Urine is collected over several hours.

- The ratio of lactulose to mannitol in the urine indicates the degree of intestinal permeability. A higher ratio of lactulose suggests increased permeability (the larger molecule is getting through more easily).

While this test can indicate increased permeability, it doesn’t necessarily diagnose a specific syndrome or pinpoint the underlying cause. It’s one piece of information that a healthcare provider might use alongside a person’s history, symptoms, and other lab tests.

Treatment Approaches for Leaky Gut

Addressing increased intestinal permeability typically involves a comprehensive approach focused on removing harmful factors, repairing the gut lining, and restoring healthy gut function. This often involves the “4 R” program framework used by many functional medicine practitioners:

- Remove: Identify and remove triggers damaging the gut.

- Eliminate inflammatory foods (start with common culprits like gluten, dairy, sugar, processed foods).

- Address infections (SIBO, yeast overgrowth, parasites) with appropriate therapies under medical supervision.

- Identify and reduce exposure to environmental toxins.

- Review medications with a doctor to see if alternatives exist, especially for NSAIDs or frequent antibiotic use.

- Replace: Replace essential components needed for digestion and absorption.

- Consider digestive enzymes to help break down food properly.

- Stomach acid support (e.g., betaine HCL, if indicated) to improve digestion.

- Replace beneficial bacteria that have been lost or are out of balance.

- Repair: Provide nutrients and compounds that help heal the gut lining.

- L-Glutamine: An amino acid that is a primary fuel source for intestinal cells.

- Zinc: Crucial for maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier.

- Bone Broth: Contains gelatin, collagen, and amino acids that can support gut tissue repair.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Help reduce inflammation.

- Aloe Vera or Deglycyrrhizinated Licorice (DGL): Can soothe the gut lining.

- Reinoculate: Restore a healthy balance of gut bacteria.

- Consume probiotic-rich foods (fermented foods like sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, yogurt – choose those appropriate for individual tolerances).

- Take a high-quality probiotic supplement containing diverse strains.

- Include prebiotic fibers in the diet (foods like garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, unripe bananas, oats, apples) to feed beneficial bacteria.

Beyond the 4 R’s, lifestyle factors are critical:

- Stress Management: Techniques like meditation, yoga, deep breathing, or mindfulness can significantly impact gut health.

- Adequate Sleep: Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night, as poor sleep impacts gut function and inflammation.

- Regular Exercise: Moderate exercise supports healthy gut motility and can positively influence the gut microbiome.

Embarking on a gut-healing journey requires patience, consistency, and often, professional guidance. It’s not a quick fix, but a process of supporting the body’s natural ability to heal.

Here’s a summary of key aspects:

| Category | Examples / Description |

| Causes | Processed foods, high sugar, low fiber, NSAIDs, antibiotics, chronic stress, infections (Candida, SIBO), environmental toxins. |

| Potential Symptoms | Digestive issues (bloating, gas, IBS), fatigue, skin problems, joint pain, brain fog, food sensitivities. |

| Treatment Pillars | Remove triggers, Replace digestive aids, Repair gut lining, Reinoculate beneficial bacteria, Lifestyle changes (stress, sleep). |

“All disease begins in the gut.” – A statement often attributed to Hippocrates, highlighting the ancient recognition of the gut’s central role in health.

Conclusion