Understanding Bloating and Trapped Air in the Upper Digestive Tract

Bloating represents one of the most common gastrointestinal complaints worldwide, affecting people of all ages and backgrounds. This uncomfortable sensation of fullness, tightness, or swelling in the abdomen can range from mildly annoying to severely debilitating. While many experience bloating as a lower abdominal issue, a significant number of individuals struggle with air that becomes trapped in the upper digestive tract, specifically between the stomach and mouth, involving the esophagus and larynx. This particular manifestation can be especially distressing, causing discomfort, difficulty swallowing, breathing concerns, and social embarrassment. Understanding the mechanisms behind this phenomenon and exploring effective management strategies can significantly improve quality life for those affected.

The Human Digestive System and Air Passage

The human digestive system represents a complex network of organs working in harmony to process food, absorb nutrients, and eliminate waste. Within this system, air naturally enters and exits through various pathways. Swallowing air, known as aerophagia, occurs during eating, drinking, speaking, and even breathing. Under normal circumstances, this air travels down the esophagus into the stomach, where it either continues through the digestive tract to be expelled as flatulence or returns upward through the esophagus and out of the mouth as a belch. However, when this natural process becomes disrupted, air can become trapped at various points along this pathway, leading to discomfort and distress.

The Role of the Esophagus and Larynx in Air Trapping

The upper digestive tract, particularly the esophagus and larynx area, presents unique challenges when air becomes trapped. The esophagus, a muscular tube connecting the throat to the stomach, normally propels food downward through coordinated muscular contractions known as peristalsis. When air instead of food becomes stuck in this tube, it can create a painful pressure that may feel like a lump in the throat or chest tightness. The larynx, or voice box, sits at the top of the trachea and plays a crucial role in breathing, swallowing, and speaking. When air accumulates near this structure, it can trigger the gag reflex, cause voice changes, or create a sensation that something is stuck in the throat, a condition known as globus pharyngeus.

Common Causes of Trapped Air in the Upper Digestive Tract

Several factors contribute to the development of trapped air in the upper digestive tract. Dietary habits rank among the most significant culprits. Eating too quickly, talking while eating, chewing gum, drinking carbonated beverages, and consuming certain gas-producing foods can all increase the amount of air swallowed. Additionally, poor posture during meals can compress the digestive tract, making it more difficult for air to pass through normally. Anxiety and stress also play a substantial role, as they often lead to unconscious air swallowing and can affect the functioning of the lower esophageal sphincter, the muscular valve that separates the esophagus from the stomach.

Medical Conditions Associated with Air Trapping

Medical conditions can also predispose individuals to experience trapped air in the upper digestive tract. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) commonly coexists with excessive belching and air trapping. In this condition, the lower esophageal sphincter weakens or relaxes inappropriately, allowing stomach contents to flow back into the esophagus. This reflux can trigger spasms in the esophageal muscles, creating pockets where air becomes trapped. Hiatal hernias, where a portion of the stomach pushes upward through the diaphragm, can also interfere with normal air passage and contribute to bloating and discomfort.

Understanding Supragastric Belching

Another condition worth noting is supragastric belching, a behavioral disorder where individuals repeatedly suck air into the esophagus and immediately expel it, often without awareness. This cycle can become habitual and may be triggered by anxiety or as a learned response to normal digestive sensations. Unlike typical belching, which originates from the stomach, supragastric belching involves air that never reaches the stomach, instead becoming trapped in the esophagus before being expelled.

Symptoms of Trapped Air in the Upper Digestive Tract

The symptoms of trapped air in the upper digestive tract can be varied and distressing. Many individuals report a persistent feeling of fullness or pressure in the chest or throat, often described as a bubble or lump that cannot be dislodged. This sensation may worsen after eating or drinking, particularly with carbonated beverages. Some experience difficulty swallowing, known as dysphagia, or pain when swallowing, called odynophagia. The trapped air can also cause excessive burping that may provide only temporary relief before the pressure builds again.

Breathing Difficulties and Chest Sensations

Breathing difficulties sometimes accompany trapped air in the upper digestive tract, though this symptom warrants careful evaluation to rule out more serious conditions. Some individuals report shortness of breath or a sensation that they cannot take a full breath due to the pressure in their chest. Others may experience chest pain that can be mistaken for cardiac issues, leading to unnecessary anxiety and medical visits. Voice changes, such as hoarseness or a weak voice, can occur when the trapped air affects the function of the larynx and vocal cords.

The Psychological Impact of Chronic Air Trapping

The psychological impact of chronic air trapping should not be underestimated. Many individuals feel self-conscious about excessive belching or the visible abdominal distension that can accompany bloating. Social situations involving meals become sources of anxiety rather than enjoyment. The constant discomfort and preoccupation with symptoms can lead to decreased quality of life, social withdrawal, and even symptoms of depression or anxiety. This psychological distress can, in turn, exacerbate the physical symptoms, creating a vicious cycle that can be challenging to break.

Diagnosing the Causes of Trapped Air

Diagnosing the cause of trapped air in the upper digestive tract typically begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination. Healthcare providers will ask detailed questions about symptom patterns, dietary habits, stress levels, and any accompanying symptoms. Keeping a symptom diary can be invaluable in this process, helping to identify triggers and patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed. In some cases, additional diagnostic tests may be necessary. These might include endoscopy, where a flexible tube with a camera is used to examine the esophagus and stomach, or imaging studies such as X-rays or CT scans to visualize the digestive tract.

Advanced Diagnostic Techniques

Manometry, a test that measures the pressure and pattern of muscle contractions in the esophagus, can help identify motility disorders that might contribute to air trapping. pH monitoring may be used to assess for acid reflux, which can cause esophageal spasms and contribute to symptoms. In cases where supragastric belching is suspected, specialized monitoring with impedance testing can differentiate between gastric and supragastric belching patterns, guiding treatment approaches.

Dietary Modifications for Managing Trapped Air

Managing trapped air in the upper digestive tract often requires a multifaceted approach that addresses both physical and behavioral factors. Dietary modifications represent a cornerstone of treatment. Eating slowly and mindfully, chewing food thoroughly, and avoiding talking while eating can significantly reduce the amount of air swallowed. Carbonated beverages should be eliminated, as they introduce additional gas into the digestive system. Identifying and avoiding personal trigger foods through an elimination diet can help reduce symptoms. Common culprits include beans, cabbage, broccoli, onions, and whole grains, though triggers vary significantly among individuals.

The Importance of Posture During Meals

Posture during and after meals plays a crucial role in managing trapped air. Sitting upright while eating and remaining upright for at least thirty minutes after meals can help prevent air from becoming trapped in the upper digestive tract. Avoiding tight clothing that compresses the abdomen can also facilitate normal air passage. Some individuals find relief from gentle movement after meals, such as short walks, which can help stimulate digestion and encourage air to move through the digestive tract.

Behavioral Interventions and Retraining Techniques

Behavioral interventions can be particularly effective, especially when supragastric belching or anxiety-related air swallowing is suspected. Speech therapy techniques can help retrain swallowing patterns and reduce unconscious air intake. Diaphragmatic breathing exercises can strengthen the diaphragm and improve control over the belching reflex. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be beneficial for individuals whose symptoms are exacerbated by anxiety or stress, helping to break the cycle of symptom preoccupation and distress.

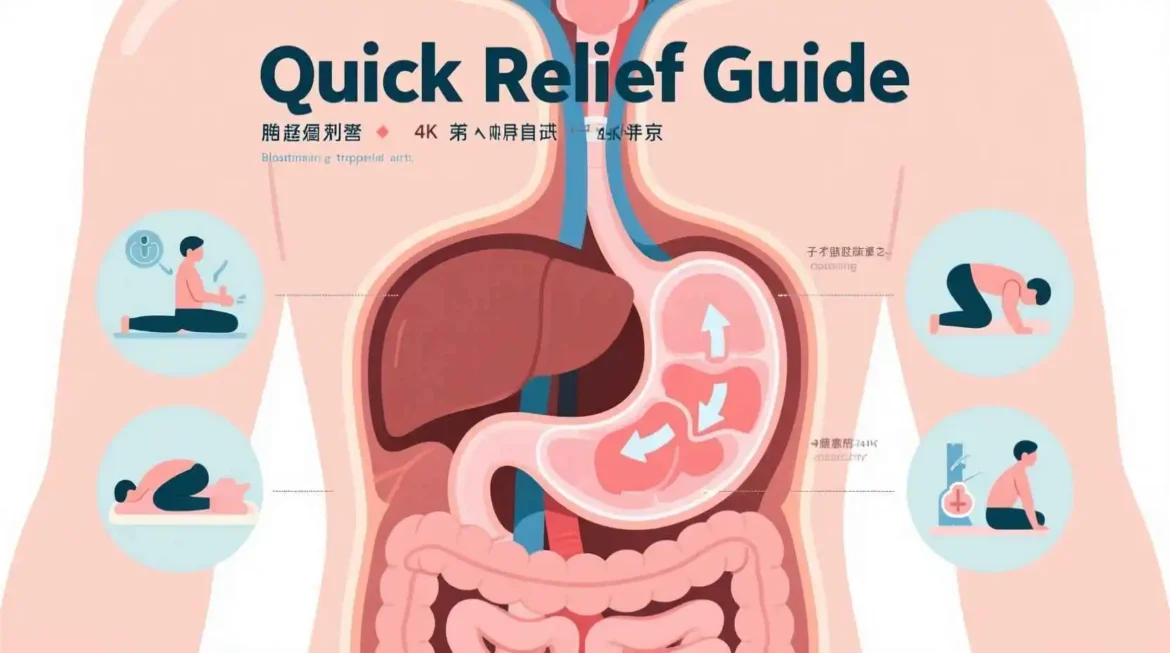

Physical Maneuvers to Release Trapped Air

Physical maneuvers can sometimes help release trapped air when it becomes stuck in the esophagus. Drinking a glass of warm water can help stimulate peristalsis and move air through the digestive tract. Gentle stretching, particularly yoga poses that open the chest and abdomen, may create space for air to pass. Some individuals find relief from specific positions, such as kneeling with the upper body forward or lying on the left side, which can help reposition the stomach and facilitate air release.

Medications and Their Role in Symptom Relief

Over-the-counter medications may provide temporary relief for some individuals. Simethicone, an anti-foaming agent, can help break up gas bubbles in the digestive tract, making them easier to expel. Antacids may help if acid reflux is contributing to symptoms, while digestive enzymes can aid in the breakdown of certain foods that might otherwise produce gas. However, these medications address symptoms rather than underlying causes and should not be relied upon as a long-term solution without addressing contributing factors.

Medical Treatments for Underlying Conditions

For individuals with underlying medical conditions contributing to trapped air, targeted treatments are essential. Proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers may be prescribed for GERD to reduce acid production and allow the esophagus to heal. In cases of significant esophageal motility disorders, medications that affect muscle function may be considered. Hiatal hernias that cause severe symptoms may require surgical intervention in some cases, though this is typically reserved for when conservative measures have failed.

The Mind-Body Connection in Managing Symptoms

The mind-body connection plays a significant role in managing trapped air in the upper digestive tract. Stress management techniques such as meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness can help reduce anxiety-related air swallowing and muscle tension that might contribute to symptoms. Regular moderate exercise can improve digestion, reduce stress, and help maintain healthy digestive function. Adequate sleep is also crucial, as sleep deprivation can exacerbate digestive symptoms and increase sensitivity to discomfort.

Alternative and Complementary Therapies

Alternative and complementary therapies may offer additional relief for some individuals. Acupuncture has shown promise in reducing symptoms of bloating and improving digestive function in some studies. Herbal remedies such as peppermint oil, ginger, and chamomile have traditionally been used to ease digestive discomfort, though scientific evidence varies. Probiotics may help balance gut bacteria and reduce gas production, particularly in individuals with dysbiosis or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Living with Chronic Trapped Air

Living with chronic trapped air in the upper digestive tract requires developing coping strategies and realistic expectations. Symptoms may fluctuate over time, with periods of improvement followed by exacerbations. Understanding that complete elimination of symptoms may not be possible but that significant improvement is achievable can help maintain motivation and prevent discouragement. Support groups, either in-person or online, can provide valuable emotional support and practical tips from others experiencing similar challenges.

Prevention Strategies and Long-Term Management

Prevention of trapped air in the upper digestive tract focuses on identifying and addressing individual triggers. This may involve ongoing attention to eating habits, stress management, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Regular check-ins with healthcare providers can help monitor symptoms and adjust treatment approaches as needed. For many, managing this condition becomes a lifelong journey of self-awareness and adaptation rather than a problem to be permanently solved.

The Impact of Mindful Eating on Air Trapping

The practice of mindful eating—paying full attention to the sensory experience of eating, chewing slowly, and savoring each bite—can dramatically reduce air swallowing. This approach not only decreases the amount of air taken in but also improves digestion by allowing the body’s natural digestive processes to function optimally. The enzyme amylase in saliva begins breaking down carbohydrates in the mouth, and thorough chewing creates more surface area for digestive enzymes to work effectively.

Foods and Beverages That Worsen Symptoms

Specific foods deserve special attention when addressing trapped air. Fatty foods can delay stomach emptying, increasing the likelihood that air will become trapped as digestion slows. High-fiber foods, while generally healthy, can produce significant gas as they’re broken down by gut bacteria. Introducing fiber gradually and drinking plenty of water can help minimize this effect. Artificial sweeteners, particularly sugar alcohols like sorbitol and xylitol, are poorly absorbed and can ferment in the gut, producing gas. Reading labels and being aware of these ingredients can prevent unnecessary discomfort.

The Role of Hydration in Digestive Health

The role of hydration in managing trapped air is often overlooked. Drinking adequate water throughout the day helps maintain healthy digestive function and can prevent constipation, which can contribute to bloating and discomfort. However, the timing of fluid intake matters. Drinking large quantities of water during meals can dilute digestive enzymes and increase the likelihood of swallowing air. Instead, sipping small amounts during meals and hydrating primarily between meals represents a more optimal approach.

Gut Microbiome and Its Influence on Gas Production

The connection between gut health and trapped air extends beyond simple gas production. The gut microbiome, the complex ecosystem of bacteria living in our digestive tract, plays a crucial role in digestion, immune function, and even mood regulation. Imbalances in this microbiome, known as dysbiosis, can lead to increased gas production and altered gut motility. Factors that can disrupt the gut microbiome include antibiotic use, stress, poor diet, and certain medical conditions. Supporting a healthy microbiome through a varied diet rich in plant foods, fermented foods, and prebiotics can help reduce symptoms of trapped air over time.

Understanding Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) represents a specific condition that can cause significant bloating and gas symptoms. In SIBO, excessive bacteria grow in the small intestine, where they normally exist in much smaller numbers. These bacteria ferment food particles, producing hydrogen, methane, or both gases. This condition often requires specific testing and treatment with antibiotics or herbal antimicrobials, followed by strategies to prevent recurrence. Many individuals with chronic bloating and trapped air symptoms may benefit from evaluation for SIBO, particularly if other treatments have provided limited relief.

Physical Techniques for Releasing Trapped Air

When air becomes stuck in the esophagus, specific maneuvers can help stimulate the muscles to move it along. The “supraglottic swallow” technique, often taught by speech therapists, involves holding the breath while swallowing, which can help close the airway and encourage air to move downward rather than upward. Gentle self-massage of the neck and upper chest area may help relax tense muscles that could be contributing to the sensation of trapped air. Some individuals find relief from the “water swallow method”—drinking a glass of warm water while holding the breath and bending forward at the waist, which can help reposition air bubbles and encourage their release.

Addressing Health Anxiety and Hypervigilance

Health anxiety, or hypervigilance about bodily sensations, can amplify the perception of discomfort and create a feedback loop where anxiety about symptoms leads to increased air swallowing and muscle tension. This pattern can become entrenched over time, with individuals developing conditioned responses to normal digestive sensations. Addressing these psychological components through therapy, stress reduction techniques, and education about the benign nature of most trapped air symptoms can be as important as addressing the physical aspects.

The Importance of Sleep Hygiene

Sleep hygiene plays an unexpected but significant role in managing trapped air. Poor sleep quality or insufficient sleep can affect digestive function in multiple ways. Sleep deprivation can increase stress hormones, alter gut motility, and heighten sensitivity to discomfort. Additionally, lying flat during sleep can exacerbate acid reflux and make it more difficult for trapped air to find its way out. Elevating the head of the bed by a few inches and avoiding large meals close to bedtime can help minimize these issues. Establishing a regular sleep schedule and creating a relaxing bedtime routine can support both digestive health and overall well-being.

Medication Side Effects and Digestive Discomfort

Many common medications can affect digestive function and contribute to bloating and gas symptoms. Certain pain relievers, particularly nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can irritate the digestive tract and alter motility. Some antibiotics can disrupt the gut microbiome, leading to increased gas production. Medications that affect muscle function, such as certain blood pressure drugs or antispasmodics, can influence the movement of air through the digestive tract. When experiencing persistent trapped air, it’s worth reviewing all medications with a healthcare provider to identify potential contributors.

Posture and Digestive Function