Diverticulitis Explained: When Digestive Pouches Turn Painful

As we navigate the complexities of our digestive system, we sometimes encounter conditions that can significantly impact our quality of life. One such condition, increasingly prevalent in modern society, is diverticulitis. It’s a term many of us might have heard, perhaps from a friend, family member, or even a medical professional, but its intricacies remain a mystery to most. Today, we aim to shed light on this common gastrointestinal disorder, exploring its origins, the signs we should watch for, how it’s identified, and the various approaches we take to manage and treat it. Understanding diverticulitis is crucial for both prevention and effective management, allowing us to maintain our digestive health and overall well-being.

What is Diverticulitis?

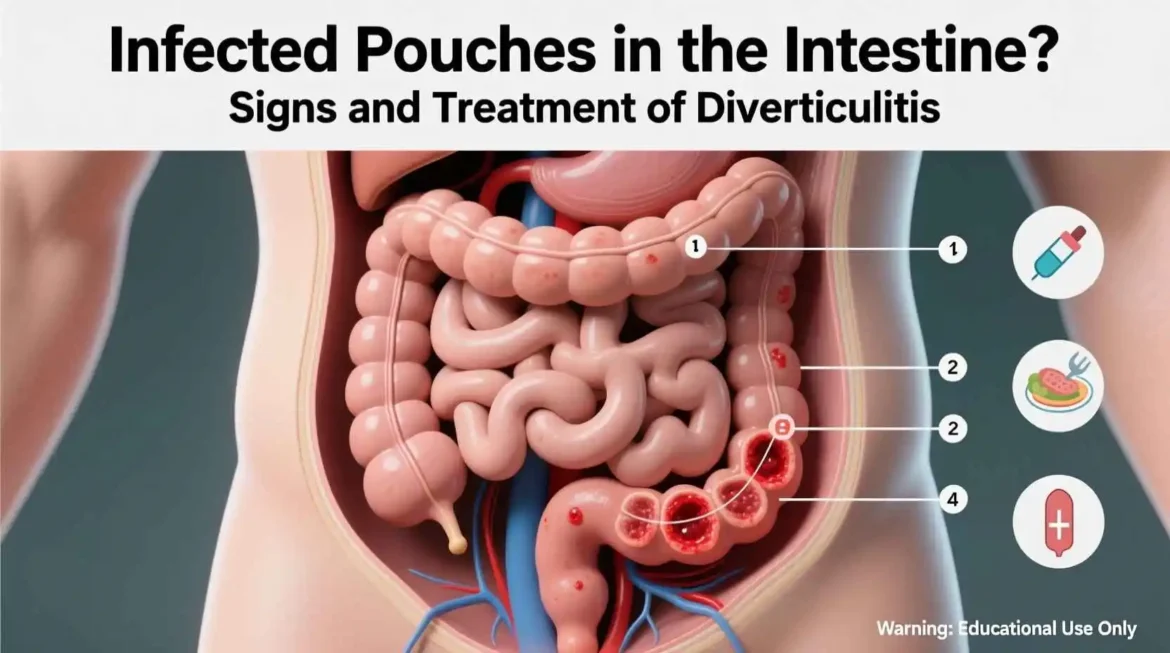

To truly grasp diverticulitis, it’s essential to first understand its silent, often undetected precursor: diverticulosis. This is a remarkably common condition, particularly as we age, where small, bulging pouches, known as diverticula, develop in the lining of the digestive tract. These pea-sized or marble-sized sacs are most frequently found in the wall of the large intestine, specifically the sigmoid colon (the S-shaped part that connects to the rectum).

The formation of these diverticula is largely attributed to increased pressure within the colon. This pressure often arises from straining during bowel movements, a common issue for individuals consuming a diet low in fiber. A diet lacking sufficient fiber leads to smaller, harder stools, requiring more effort for the colon to move them along. Over years, this consistent high pressure can cause weak spots in the colon wall to bulge outward, forming diverticula. For the vast majority of people, diverticulosis causes no noticeable symptoms whatsoever. It’s often an incidental finding during a routine colonoscopy or other abdominal imaging performed for different reasons. You can have diverticulosis for decades without ever knowing it.

Diverticulitis, however, is a different story. It represents an acute and often painful complication that occurs when one or more of these previously harmless diverticula become inflamed or infected. This critical shift happens when tiny bits of undigested food, fecal matter, or even mucus get trapped within the narrow opening of a diverticulum. This trapped material acts as an irritant, leading to inflammation within the pouch. If bacteria multiply within this inflamed pouch, it can quickly develop into a localized infection.

While diverticulosis is prevalent – affecting a significant portion of the population over 60 – only a relatively small percentage of individuals with diverticulosis will go on to develop diverticulitis. When it does occur, the symptoms can range from mild to severe and often include:

- Sudden, persistent abdominal pain, most commonly in the lower left side (where the sigmoid colon is located).

- Tenderness in the affected area, which may worsen with touch.

- Fever and chills, indicating an infection.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Changes in bowel habits, such as constipation or, less commonly, diarrhea.

- Bloating.

In severe cases, if left untreated, diverticulitis can lead to more serious complications like an abscess (a pocket of pus), a fistula (an abnormal connection between organs), a bowel obstruction, or even perforation of the colon, which can be life-threatening. Therefore, prompt medical attention is crucial if diverticulitis is suspected.

The Complex Etiology of Diverticulitis: Unraveling the Contributing Factors

While the precise pathophysiological mechanisms leading to diverticulitis remain an area of ongoing research, it is widely recognized as a complex condition stemming from a confluence of interconnected risk factors. Understanding these contributing elements is crucial for both prevention and management strategies, as they often interact synergistically to increase an individual’s susceptibility. Diverticulitis typically arises when one or more small, pouch-like protrusions (diverticula) in the colon become inflamed or infected.

Here are some of the primary contributing factors currently considered by medical professionals:

- Low-Fiber Diet: Historically and still widely considered a significant contributor, a long-term diet deficient in dietary fiber is strongly implicated. Insufficient fiber intake leads to smaller, harder, and more difficult-to-pass stools. This necessitates increased muscular effort and heightened intraluminal pressure within the colon during defecation. Over time, this chronic elevated pressure can cause small, sac-like pouches (diverticula) to protrude through weak spots in the colonic wall, a condition known as diverticulosis. While the direct causal link between low fiber and inflammation (diverticulitis) is now viewed with more nuance – acknowledging other factors like inflammation and microbiome – a high-fiber diet remains foundational for promoting regular bowel movements, reducing colonic pressure, and maintaining overall gut health.

- Age: Advancing age is one of the most significant and consistent risk factors. The incidence of diverticulosis, the precursor to diverticulitis, rises sharply with each decade of life. It is estimated that over 50% of individuals by age 60, and up to 70% by age 80, harbor diverticula. This heightened susceptibility in older populations is thought to be due to an age-related weakening of the colonic muscle wall, cumulative exposure to other risk factors over time, and potentially age-related changes in gut motility and the microbiome.

- Obesity: Excess body weight, particularly obesity (Body Mass Index [BMI] of 30 or higher), is increasingly recognized as a potent risk factor. Obese individuals, especially those with abdominal obesity, exhibit a significantly elevated risk of developing diverticulitis, including more severe or complicated forms, and often at a younger age. The mechanisms are believed to involve chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, altered gut microbiota composition, and potentially mechanical stress on the colon.

- Lack of Physical Activity: A sedentary lifestyle and insufficient physical activity are associated with a higher incidence of diverticular disease. Regular exercise helps promote normal bowel function, increases gut motility (peristalsis), and reduces colonic transit time, thereby preventing constipation and decreasing intraluminal pressure. Conversely, inactivity can lead to sluggish bowel movements and prolonged transit, contributing to the conditions favorable for diverticula formation and potential inflammation.

- Smoking: Cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor for diverticulitis. Studies have consistently demonstrated that current smokers have a higher likelihood of developing the condition, and potentially more severe outcomes, compared to non-smokers. The proposed mechanisms include impaired blood flow to the colon, promotion of chronic inflammation, and alterations in the gut microbiota.

- Certain Medications: The long-term or regular use of certain pharmacological agents has been linked to an increased risk of diverticulitis and its complications. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin are thought to contribute by potentially causing microscopic damage to the intestinal lining, impairing local immune responses, and altering gut permeability. Corticosteroids, powerful anti-inflammatory drugs, can suppress the immune system and potentially obscure symptoms, leading to delayed diagnosis. Opioid analgesics are well-known for their constipating effect, which can significantly increase intraluminal pressure and prolong stool transit time, thereby exacerbating the risk.

- Genetics: While not as clearly defined as environmental factors, there is growing evidence supporting a genetic predisposition to diverticular disease. Individuals with a first-degree relative (parent, sibling) who has had diverticulosis or diverticulitis are at an increased risk. Research is exploring specific genetic variants that may influence the strength of the colonic wall, immune responses, or gut motility, thereby contributing to susceptibility.

- Gut Microbiome Imbalance: This is a rapidly evolving area of research. An imbalance in the composition and function of the gut microbiota, a condition known as dysbiosis, is increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis. A disrupted microbiome can lead to chronic low-grade inflammation in the colon, impaired gut barrier function, and altered metabolism of dietary components, all of which may contribute to the initiation or exacerbation of diverticular inflammation. The complex interplay between the host immune system and the gut microbes is a key focus of current investigations.

In summary, diverticulitis is not simply caused by a single factor but rather emerges from a complex interplay of genetic predispositions, lifestyle choices, environmental exposures, and alterations within the gut microenvironment. A holistic approach to understanding these influences is essential for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies.

Recognizing the Symptoms

Recognizing the symptoms of diverticulitis is of paramount importance for prompt diagnosis and effective management. The clinical presentation can vary significantly, ranging from mild, transient discomfort that might initially be dismissed, to severe, debilitating pain that necessitates immediate medical attention. The intensity and nature of the signs are largely dependent on the extent of the inflammation, whether an infection is present, and if any complications have arisen.

Here are the common symptoms healthcare providers typically look for:

- Abdominal Pain: This is by far the most prevalent and often the first symptom reported. It classically localizes to the lower-left side of the abdomen, as the sigmoid colon (the most common site for diverticula) is located there. However, it’s crucial to note that the pain can sometimes manifest on the right side, especially in individuals of Asian descent or those with atypical abdominal anatomy. The pain’s onset can be quite sudden and severe, or it may begin mildly, perhaps as a crampy ache, gradually worsening over several days. A key characteristic is its persistence; unlike gas pain or menstrual cramps, it usually doesn’t ease significantly after a bowel movement or the passing of gas. It might be further exacerbated by movement, coughing, or straining.

- Fever and Chills: The presence of a fever (an elevated body temperature) often accompanied by chills or shivering, serves as a strong indicator of an infection within the diverticula. This systemic response suggests the body’s immune system is actively fighting off bacteria that have proliferated in the inflamed pouches. The degree of fever can sometimes correlate with the severity of the infection.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Many individuals experiencing diverticulitis report feelings of nausea, which can progress to vomiting. These symptoms are often a direct result of the significant inflammation in the digestive tract, which can disrupt normal bowel function and cause general malaise. Vomiting can lead to dehydration if severe or prolonged.

- Change in Bowel Habits: The inflammatory process in diverticulitis frequently impacts the normal rhythm of bowel movements. This most commonly manifests as constipation, where the inflamed and swollen colon can narrow, making stool passage difficult. Less commonly, some individuals may experience diarrhea, possibly due to irritation and increased motility in the affected segment of the bowel. Patients often also report significant abdominal tenderness upon palpation, along with a noticeable sense of bloating or distension.

- Abdominal Tenderness: The area of the abdomen directly over the inflamed diverticula is typically very tender to the touch. This tenderness is localized and can be sharp, indicating the presence of underlying inflammation or infection. In more severe cases, or if peritonitis is suspected, rebound tenderness (pain that is worse when pressure is quickly released from the abdomen) may be observed.

- Rectal Bleeding: While less common than the other symptoms, some individuals may experience mild rectal bleeding. This usually appears as bright red blood in small amounts, mixed with stool or on toilet paper. It typically results from the erosion of small blood vessels within the inflamed diverticula. However, any significant rectal bleeding warrants immediate medical attention, as it could signal a more serious complication such as a ruptured blood vessel or another underlying gastrointestinal condition.

In more severe and potentially life-threatening cases, referred to as complicated diverticulitis, we may observe signs of:

- Abscess Formation: This involves the development of a localized collection of pus within the abdomen, usually adjacent to the inflamed diverticulum. An abscess can cause persistent or worsening localized pain, higher fever, and a palpable lump or mass in the abdomen.

- Perforation: This is a critical medical emergency where the inflamed diverticulum ruptures, leading to a tear in the bowel wall. This allows bowel contents (stool and bacteria) to leak into the abdominal cavity, causing a widespread and severe infection known as peritonitis. Symptoms include sudden, excruciating, diffuse abdominal pain, a rigid, board-like abdomen, high fever, and signs of septic shock. Immediate surgical intervention is required.

- Fistula Formation: A fistula is an abnormal tunnel or connection that forms between the colon and another organ or the skin, due to chronic inflammation eroding through adjacent tissues. Common types include colovesical fistulas (between the colon and bladder, leading to recurrent urinary tract infections, air in urine, or fecaluria) or colocutaneous fistulas (to the skin, resulting in discharge of pus or stool).

- Bowel Obstruction: Severe inflammation, repeated episodes of diverticulitis, or scarring can lead to a narrowing (stricture) of the colon’s lumen. This stricture can impede the normal passage of stool and gas, leading to a partial or complete bowel obstruction. Symptoms include severe cramping abdominal pain, distension, inability to pass gas or stool, and persistent vomiting.

Diagnosing Diverticulitis

Prompt recognition and accurate diagnosis of these symptoms are crucial, as early intervention can prevent the progression to these severe complications and significantly improve patient outcomes. If any of these symptoms are experienced, especially persistent abdominal pain, fever, or significant changes in bowel habits, it is imperative to seek medical evaluation without delay.

When we suspect diverticulitis based on symptoms, a thorough diagnostic process is essential to confirm the diagnosis, rule out other conditions (like appendicitis, irritable bowel syndrome, or colon cancer), and assess the severity.

The diagnostic approach typically involves:

The comprehensive diagnostic approach is designed to accurately identify diverticulitis, assess its severity, and rule out other conditions that might present with similar symptoms. This multi-faceted process typically involves a combination of thorough clinical evaluation, specific laboratory tests, and advanced imaging studies, ensuring we gather all necessary information to formulate the most appropriate treatment plan for you.

A detailed breakdown of the diagnostic steps:

- Clinical Evaluation: A Foundation for Diagnosis

- Medical History: Our initial step involves a detailed discussion about your medical history. We will carefully inquire about your current symptoms, including their precise onset, duration, intensity (mild, moderate, severe), and any patterns or triggers. It’s crucial for us to know if you’ve experienced similar episodes in the past and how they were managed. Furthermore, we’ll delve into your dietary habits, current and recent medication use (including over-the-counter drugs and supplements), and a comprehensive review of your family medical history, as certain gastrointestinal conditions can have a genetic predisposition.

- Physical Examination: A thorough physical examination is then conducted. This involves carefully assessing your abdomen for areas of tenderness, particularly focusing on the lower left quadrant, which is a common site for diverticulitis pain. We will also palpate for any masses, distension, or rigidity. Beyond the abdomen, we will check your vital signs like temperature (to detect fever), heart rate, and blood pressure, looking for any signs of systemic inflammation or infection that might indicate a more severe condition.

- Laboratory Tests: Uncovering Internal Clues

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): A Complete Blood Count (CBC) is a standard diagnostic tool. We will specifically look for an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, also known as leukocytosis. A significant increase in WBCs is a strong indicator of an ongoing infection or acute inflammatory process within the body, characteristic of diverticulitis.

- C-reactive protein (CRP): C-reactive protein (CRP) is another valuable blood test. CRP is an acute-phase reactant, meaning its levels rise rapidly in response to inflammation. An elevated CRP level provides objective evidence of systemic inflammation and helps us gauge the severity of the inflammatory response.

- Urinalysis: A Urinalysis may be performed to analyze a urine sample. The primary purpose of this test in the context of suspected diverticulitis is to rule out a urinary tract infection (UTI) or kidney stones, as these conditions can present with symptoms (like abdominal pain or fever) that mimic those of diverticulitis, ensuring an accurate diagnosis.

- Imaging Studies: Visualizing the Condition Internally These advanced imaging techniques are absolutely crucial for confirming the diagnosis of diverticulitis, assessing the precise location and extent of the inflammation, and identifying any potential complications.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: A Computed Tomography (CT) Scan of the abdomen and pelvis is widely considered the gold standard for accurately diagnosing acute diverticulitis. This sophisticated imaging technique provides detailed cross-sectional images that can clearly show inflamed and thickened areas of the colon wall (indicating diverticulitis), as well as identify critical complications such as abscesses (collections of pus), perforations (a tear in the bowel wall), fistulas, or bowel obstruction. The CT scan is invaluable in helping us definitively differentiate diverticulitis from other conditions that may cause similar symptoms, such as appendicitis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or colon cancer.

- Abdominal Ultrasound: While less commonly used as a primary diagnostic tool than CT, Abdominal Ultrasound can sometimes be a useful adjunct. This non-invasive imaging method uses sound waves to create images and can identify inflamed diverticula, wall thickening, and even abscesses in certain cases. Its primary advantage lies in its safety profile, as it does not involve radiation exposure, making it a preferred option for pregnant individuals or patients where minimizing radiation is a significant consideration.

- Colonoscopy:Colonoscopy plays a distinct and crucial role, though its timing is important. It is critically important to note that a colonoscopy is generally not performed during an acute, active attack of diverticulitis. This is due to a significant risk of causing a bowel perforation (a tear in the inflamed colon wall) or exacerbating the inflammation. However, once the acute inflammation has completely subsided – typically waiting around 6 to 8 weeks after the initial symptoms have resolved – we strongly recommend a follow-up colonoscopy. This procedure, which involves inserting a flexible tube with a camera into the colon, allows us to:

- Confirm the full extent of diverticulosis: Visualizing the number, size, and location of the diverticula throughout the colon.

- Rule out other serious gastrointestinal conditions: This is paramount. It allows us to investigate and exclude other conditions that can present with similar symptoms but require different treatments, most notably ensuring there is no underlying colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), or polyps. This is particularly vital if the individual has never had a recent colonoscopy, has a family history of colon cancer, or exhibits other risk factors for colorectal malignancies.

Together, these diagnostic tools provide a comprehensive picture of your condition, guiding us in developing the most effective and personalized treatment plan for your diverticulitis. Our approach to treating diverticulitis depends on its severity and whether complications are present. The goal is to reduce inflammation, clear infection, alleviate symptoms, and prevent future episodes.

Understanding and Managing Uncomplicated Diverticulitis