Physical activity benefits not just the body but also the brain. Exercise increases blood flow to the brain, stimulates the growth of new neurons and connections (neurogenesis and synaptogenesis), and enhances cognitive function.

Regular physical activity is associated with larger brain volume, particularly in regions responsible for memory and executive function. It also reduces the risk of cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Exercise may benefit brain health through multiple mechanisms, including reducing inflammation and oxidative stress, improving insulin sensitivity, increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and promoting better sleep.

Finding the Right Balance

While exercise is beneficial, excessive intensity or volume without adequate recovery can potentially have negative effects, including increased oxidative stress, immune suppression, and accelerated aging in certain contexts.

The optimal exercise program for longevity likely includes a balance of different types of activity, appropriate intensity and volume, and sufficient recovery. This balance should be individualized based on age, fitness level, health status, and personal preferences.

Sleep and Recovery

Sleep is a fundamental biological process essential for health, well-being, and longevity. During sleep, the body undergoes critical repair and restoration processes, the brain consolidates memories and clears waste products, and the immune system recharges. Despite its importance, sleep is often neglected in modern society, with significant consequences for health and longevity.

The Science of Sleep

Sleep occurs in cycles of different stages, including non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, which has three phases of increasing depth, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. These cycles repeat approximately every 90 minutes, with the proportion of time spent in each stage varying across the night.

Deep NREM sleep is crucial for physical restoration, growth hormone release, and cellular repair. REM sleep is important for cognitive functions like memory consolidation, learning, and emotional processing. Both stages are essential for optimal health and longevity.

Sleep is regulated by two main processes: the circadian rhythm (our internal 24-hour clock) and the homeostatic sleep drive (the accumulation of sleep pressure the longer we’re awake). Disruptions to either process can impair sleep quality and duration.

Sleep Duration and Longevity

Research consistently shows a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and mortality, with both too little and too much sleep associated with increased risk. For most adults, 7-8 hours of sleep per night appears optimal for longevity.

Short sleep duration (less than 6 hours) is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, immune dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and all-cause mortality. Chronic sleep deprivation accelerates aging processes and increases inflammation and oxidative stress.

Long sleep duration (more than 9 hours) is also associated with higher mortality, though this may reflect underlying health conditions rather than being a direct cause. Some research suggests that sleep needs may decrease slightly with age, but quality remains crucial.

Sleep Quality and Health span

Beyond duration, sleep quality is equally important for health and longevity. Quality sleep involves sufficient time in deep and REM stages, minimal awakenings, and feeling refreshed upon waking.

Poor sleep quality is associated with accelerated cellular aging, increased inflammation, impaired glucose metabolism, reduced immune function, and higher risk of chronic diseases. It also negatively impacts mood, cognitive performance, and physical functioning.

Sleep disorders like sleep apnea, which causes repeated breathing interruptions during sleep, are particularly detrimental to health. Untreated sleep apnea increases the risk of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cognitive decline.

The Glymphatic System and Brain Health

During deep sleep, the glymphatic system becomes highly active, clearing metabolic waste products from the brain. This includes beta-amyloid and tau proteins, which accumulate in Alzheimer’s disease.

Impaired glymphatic function due to poor sleep may contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases. Prioritizing deep, restorative sleep may be one of the most effective strategies for maintaining brain health and preventing cognitive decline as we age.

Strategies for Improving Sleep

Good sleep hygiene practices can significantly improve sleep quality and duration. These include:

Maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, even on weekends, helps regulate the circadian rhythm. Going to bed and waking up at the same time each day can improve sleep quality and make falling asleep and waking up easier.

Creating a sleep-conducive environment involves keeping the bedroom cool (around 65°F or 18°C), dark, and quiet. Blackout curtains, eye masks, earplugs, or white noise machines can help achieve optimal conditions.

Limiting exposure to blue light from screens in the evening is important, as blue light suppresses melatonin production, the hormone that regulates sleep. Using blue light filters on devices or avoiding screens for 1-2 hours before bed can help.

Establishing a relaxing bedtime routine signals to the body that it’s time to sleep. This might include activities like reading, gentle stretching, meditation, or taking a warm bath.

Avoiding stimulants like caffeine and nicotine close to bedtime is essential, as they can interfere with sleep onset and quality. While alcohol may initially induce sleep, it disrupts sleep architecture later in the night, reducing restorative deep sleep and causing awakenings.

Regular physical activity can improve sleep quality, but intense exercise close to bedtime may be stimulating for some individuals. Timing workouts earlier in the day is generally preferable for sleep.

Managing stress and anxiety through techniques like meditation, deep breathing, or journaling can help quiet a racing mind and facilitate sleep onset.

Napping and Longevity

Short naps (10-30 minutes) can provide benefits like improved alertness, mood, and cognitive performance. Some research suggests that regular short naps may be associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk and mortality.

However, long or frequent naps, especially late in the day, can interfere with nighttime sleep quality and duration. For most adults, limiting naps to early afternoon and keeping them brief is optimal.

The Future of Sleep Science

Emerging research is exploring the relationship between sleep and longevity at a molecular level. Studies are investigating how sleep affects telomere length, epigenetic aging clocks, and other biomarkers of aging.

As our understanding of sleep’s role in health and aging grows, personalized approaches to sleep optimization may become an integral part of longevity medicine.

Stress Management and Mental Health

Chronic stress accelerates aging and negatively impacts health span through multiple physiological pathways. While acute stress is a natural and sometimes beneficial response, prolonged activation of stress systems can damage nearly every organ system in the body. Effective stress management and mental health care are essential components of any longevity strategy.

The Physiology of Stress

When we encounter a stressor, the body activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system, triggering the “fight-or-flight” response. This releases stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and blood glucose while suppressing non-essential functions like digestion and immune response.

In acute situations, this response is adaptive, helping us respond to threats. However, chronic activation of these systems leads to dysregulation, with persistently elevated cortisol levels, inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular damage.

Chronic Stress and Accelerated Aging

Chronic stress has been linked to accelerated aging at the cellular level. Studies have shown that individuals experiencing chronic psychological stress have shorter telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes that shorten with each cell division.

Stress also promotes epigenetic aging, changes in gene expression patterns that reflect biological age rather than chronological age. These changes can persist even after the stressor is removed, potentially having long-term effects on health and longevity.

The inflammation caused by chronic stress contributes to the development of age-related diseases like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders. Stress also impairs immune function, making us more susceptible to infections and potentially reducing cancer surveillance.

Stress and Health Behaviors

Beyond its direct physiological effects, chronic stress often leads to unhealthy behaviors that further accelerate aging. These include poor dietary choices, physical inactivity, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and inadequate sleep.

Stress can also affect cognitive function, impairing decision-making, memory, and emotional regulation. This can create a vicious cycle where stress leads to poor choices that increase stress levels, further compromising health and longevity.

Effective Stress Management Techniques

Fortunately, numerous evidence-based strategies can help mitigate the negative effects of stress and promote resilience. These include:

Mindfulness meditation involves paying attention to the present moment without judgment. Regular practice has been shown to reduce stress, lower cortisol levels, decrease inflammation, and even slow cellular aging by increasing telomerase activity, the enzyme that replenishes telomeres.

Deep breathing exercises activate the parasympathetic nervous system, counteracting the stress response. Techniques like diaphragmatic breathing, box breathing (inhaling, holding, exhaling, and pausing for equal counts), and alternate nostril breathing can quickly induce relaxation.

Progressive muscle relaxation involves systematically tensing and relaxing muscle groups throughout the body. This practice reduces physical tension and promotes awareness of the difference between tension and relaxation.

Regular physical activity is one of the most effective stress reducers, improving mood, reducing anxiety and depression, and enhancing resilience to stress. Exercise also helps metabolize stress hormones and stimulates the production of endorphins, natural mood elevators.

Spending time in nature, or “forest bathing,” has been shown to reduce cortisol levels, blood pressure, and sympathetic nervous system activity while improving mood and immune function.

Social connection is a powerful buffer against stress. Strong social ties are associated with lower stress levels, better immune function, and increased longevity. Sharing experiences, receiving support, and feeling connected to others can help put stressors in perspective.

Cognitive restructuring, a component of cognitive-behavioral therapy, involves identifying and challenging negative thought patterns that contribute to stress. This technique helps develop more balanced and adaptive ways of thinking about stressful situations.

The Role of Purpose and Meaning

Having a sense of purpose or meaning in life is associated with reduced stress, better health outcomes, and increased longevity. Purpose can come from various sources, including work, relationships, creative pursuits, spiritual practices, or contributing to something larger than oneself.

Research suggests that individuals with a strong sense of purpose have lower levels of inflammation, better cardiovascular health, and reduced risk of cognitive decline and mortality. Purpose may buffer against stress by providing perspective, motivation for healthy behaviors, and psychological resilience.

Positive Psychology and Longevity

Positive psychology, the scientific study of well-being and flourishing, has identified several factors that contribute to both happiness and longevity. These include:

Gratitude practice, regularly acknowledging things one is thankful for, has been shown to reduce stress, improve sleep, enhance relationships, and strengthen immune function.

Optimism, a general expectation that good things will happen, is associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease, better immune function, and increased longevity. Optimists tend to engage in healthier behaviors and have more effective coping strategies when faced with stress.

Forgiveness, letting go of resentment and anger, reduces stress and improves psychological well-being. Studies have linked forgiveness to lower blood pressure, better sleep, and reduced risk of chronic diseases.

Laughter and humor have immediate stress-reducing effects, lowering cortisol levels and increasing endorphins. Regular laughter is associated with improved immune function, pain tolerance, and cardiovascular health.

Mental Health and Longevity

Mental health conditions like depression and anxiety are associated with increased inflammation, oxidative stress, and accelerated cellular aging. They also contribute to unhealthy behaviors and social isolation, further impacting longevity.

Treating mental health conditions through therapy, medication when appropriate, and lifestyle interventions is crucial for both quality of life and longevity. Integrating mental health care into overall health and longevity strategies is essential for optimizing health span.

Social Connections and Community

Human beings are inherently social creatures, and our connections with others play a crucial role in health and longevity. Research consistently shows that strong social ties are associated with longer life, better health outcomes, and increased resilience to stress. In contrast, social isolation and loneliness are significant risk factors for premature mortality and numerous health problems.

The Science of Social Connection

Social connection affects health through multiple physiological pathways. Positive social interactions reduce stress hormones, lower inflammation, strengthen immune function, and promote healthier behaviors. The sense of belonging and purpose that comes from meaningful relationships also contributes to psychological well-being.

Studies have found that individuals with strong social connections have lower levels of C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation), better cardiovascular health, more robust immune responses, and even longer telomeres. These biological effects may explain why social integration is such a powerful predictor of longevity.

The Health Risks of Loneliness and Isolation

Loneliness, the subjective feeling of social disconnection, and social isolation, the objective lack of social contacts, are distinct but related phenomena. Both are associated with increased risk of premature mortality comparable to well-established risk factors like smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity.

Chronic loneliness activates the same stress pathways as other threats, leading to elevated cortisol levels, increased inflammation, and impaired immune function. Over time, these physiological changes contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and other age-related conditions.

Loneliness is also associated with unhealthy behaviors like poor diet, physical inactivity, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption, further increasing health risks. The psychological distress of loneliness can lead to depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances, creating a vicious cycle that accelerates aging.

The Benefits of Diverse Social Networks

Having a diverse social network with different types of relationships (family, friends, colleagues, community members) provides varied sources of support and stimulation. Each type of connection offers unique benefits:

Family relationships often provide deep emotional bonds and practical support. Strong family ties are associated with better health outcomes and increased longevity, though the quality of relationships matters more than quantity.

Friendships offer companionship, emotional support, and opportunities for shared activities. Friends can provide different perspectives than family and may be particularly important for identity development and validation.

Community connections, including participation in religious, civic, or interest-based groups, foster a sense of belonging and purpose. Community involvement has been linked to increased longevity, possibly through multiple mechanisms including social support, meaning, and healthy behavior norms.

Intergenerational Connections

Interacting with people of different ages provides unique benefits for health and longevity. For older adults, connections with younger people can provide a sense of purpose, opportunities for knowledge transfer, and exposure to new ideas and perspectives. For younger people, relationships with older adults offer wisdom, mentorship, and historical perspective.

Intergenerational programs that bring together older and younger individuals have shown benefits for both groups, including improved attitudes, increased life satisfaction, and better health outcomes. These connections may be particularly valuable in societies where age segregation is common.

The Role of Relationships in Blue Zones

In Blue Zones, regions with exceptionally high concentrations of centenarians, strong social connections are a common feature. Okinawans maintain moais, small groups of lifelong friends who provide social and financial support throughout life. Sardinians and Ikarians live in tight-knit communities where family and social connections are central to daily life.

These long-lived populations prioritize relationships, often living in multigenerational households and participating in community activities. The social fabric of these communities provides emotional support, practical assistance, and a sense of belonging that contributes to both longevity and health span.

Cultivating Social Connection

For those looking to enhance their social connections, several strategies can be effective:

Joining groups or clubs based on personal interests provides opportunities to meet like-minded individuals and develop shared activities. These might include book clubs, hiking groups, volunteer organizations, or classes.

Volunteering offers the dual benefits of social connection and a sense of purpose. Helping others has been shown to reduce stress, increase happiness, and even lower mortality risk.

Reaching out to existing friends and family members, even with brief contacts, can strengthen relationships. Regular communication, whether in person, by phone, or through digital means, helps maintain social bonds.

Practicing active listening and empathy in interactions deepens connections and makes relationships more rewarding. Being present and engaged in conversations shows others that they are valued.

Adopting a pet can provide companionship and opportunities for social interaction with other pet owners. The human-animal bond has been shown to reduce stress and improve various health markers.

The Digital Age and Social Connection

Technology has transformed how we connect with others, offering both opportunities and challenges for social well-being. Digital communication can help maintain relationships across distances and connect individuals with shared interests who might not otherwise meet.

However, online interactions may not provide the same depth of connection as in-person contact, and excessive social media use has been linked to increased feelings of isolation and depression in some studies. Finding a balance between online and offline connections is important for optimal social health.

Environmental Factors and Longevity

Our environment plays a significant role in health and longevity, influencing everything from cellular function to behavior. Environmental factors include physical surroundings, exposure to toxins, climate, and access to healthcare and resources. Understanding and optimizing these factors can significantly impact both lifespan and health span.

Air Quality and Respiratory Health

Air pollution is a major environmental risk factor for numerous health problems and premature mortality. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and other pollutants can penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream, causing systemic inflammation and oxidative stress.

Long-term exposure to air pollution is associated with increased risk of respiratory diseases, cardiovascular disease, stroke, lung cancer, diabetes, and cognitive decline. Studies suggest that air pollution may accelerate aging at the cellular level, shortening telomeres and promoting epigenetic aging.

Improving indoor air quality through air purifiers, proper ventilation, and minimizing indoor pollutants can reduce exposure. Monitoring air quality indexes and limiting outdoor activities during high pollution days can also help. For those living in highly polluted areas, relocation to areas with cleaner air may be considered for long-term health.

Water Quality and Hydration

Access to clean, safe drinking water is essential for health and longevity. Contaminants in water sources, including heavy metals, pesticides, industrial chemicals, and pathogens, can have serious health effects ranging from acute gastrointestinal illness to chronic diseases like cancer and neurological disorders.

Water filtration systems can remove many contaminants, and testing water quality can identify potential issues. Staying adequately hydrated with clean water supports cellular function, detoxification, and overall health.

Natural Environments and Health

Exposure to natural environments, or “green spaces,” has been associated with numerous health benefits. Time in nature reduces stress, lowers blood pressure, improves mood, enhances immune function, and may even promote longevity.

The practice of “forest bathing” (shinrin-yoku in Japan), immersing oneself in a forest environment, has been shown to reduce cortisol levels, blood pressure, and heart rate while increasing parasympathetic nervous system activity. These physiological changes may contribute to the observed longevity benefits of living near green spaces.

Urban planning that incorporates parks, trees, and natural areas can provide health benefits to city dwellers. Even views of nature from windows and indoor plants have been shown to have positive effects on health and well-being.

Noise Pollution and Health

Excessive noise exposure, particularly in urban environments, is an often-overlooked environmental factor that impacts health. Chronic noise exposure has been linked to sleep disturbances, cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, and accelerated aging.

Noise activates the stress response, increasing cortisol levels and sympathetic nervous system activity. Over time, this can lead to hypertension, heart disease, and other stress-related conditions. Noise at night can disrupt sleep even without causing conscious awakenings, reducing restorative deep sleep.

Strategies to reduce noise exposure include using soundproofing in homes, choosing quieter living areas when possible, and spending time in quiet natural settings. White noise machines or apps can help mask disruptive sounds and improve sleep quality.

Light Exposure and Circadian Rhythms

Light is a powerful environmental regulator of circadian rhythms, which influence nearly every physiological process. Exposure to natural light during the day, particularly in the morning, helps maintain healthy circadian rhythms, improving sleep, mood, and metabolic health.

Conversely, exposure to artificial light at night, especially blue light from screens, can disrupt circadian rhythms and suppress melatonin production. This disruption has been linked to increased risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, mood disorders, and cancer.

Optimizing light exposure includes seeking bright natural light during the day, minimizing blue light exposure in the evening, and maintaining darkness during sleep. Using blackout curtains, eye masks, and avoiding screens before bedtime can help protect circadian health.

Environmental Toxins and Aging

We are exposed to numerous environmental toxins in daily life, including pesticides, heavy metals, industrial chemicals, and endocrine-disrupting compounds. These toxins can accumulate in the body over time, contributing to inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular damage.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and certain pesticides interfere with hormone function and have been linked to reproductive problems, obesity, diabetes, and cancer. Heavy metals like lead, mercury, and cadmium can cause neurological damage and increase oxidative stress.

Reducing exposure to environmental toxins involves choosing organic produce when possible, using natural cleaning and personal care products, avoiding plastic food containers (especially for hot foods), and ensuring proper ventilation in living spaces. Supporting the body’s natural detoxification systems through adequate hydration, fiber intake, and nutrients like sulforaphane (from cruciferous vegetables) can also help mitigate the effects of unavoidable exposures.

The Built Environment and Physical Activity

The design of our communities and neighborhoods significantly impacts physical activity levels and health. Walkable communities with sidewalks, parks, and mixed land use encourage active transportation and recreational physical activity.

Access to safe outdoor spaces for exercise and recreation is associated with higher physical activity levels, lower obesity rates, and better cardiovascular health. Conversely, neighborhoods that lack sidewalks, parks, or safe walking areas discourage physical activity and contribute to sedentary lifestyles.

Advocating for community design that promotes active living and taking advantage of existing opportunities for physical activity in the environment can support longevity. This might include walking or cycling for transportation, using stairs instead of elevators, and participating in outdoor recreational activities.

Climate and Longevity

Climate influences health through multiple pathways, including temperature extremes, weather patterns, and seasonal variations in daylight and activity. Extreme heat events are associated with increased mortality, particularly among older adults and those with chronic health conditions.

Climate change is emerging as a significant threat to human health and longevity, with impacts including more frequent and intense heat waves, extreme weather events, changes in infectious disease patterns, and threats to food and water security.

Adapting to climate challenges through appropriate housing, clothing, and behavior can help mitigate risks. This includes staying hydrated during hot weather, maintaining proper heating in cold climates, and being prepared for extreme weather events.

Emerging Longevity Science and Technologies

The field of longevity science is rapidly advancing, with new discoveries and technologies offering unprecedented insights into the aging process and potential interventions to extend both lifespan and health span. From genetic research to regenerative medicine, these emerging approaches may revolutionize how we understand and address aging in the coming decades.

Genetic and Epigenetic Approaches

Genetic factors account for approximately 20-30% of lifespan variation, with the rest attributed to environmental and lifestyle factors. However, understanding the genetic components of longevity can provide valuable insights into aging mechanisms and potential interventions.

Longevity genes like FOXO3, APOE, and CETP have been identified in human populations with exceptional longevity. These genes influence various biological processes including DNA repair, inflammation, lipid metabolism, and cellular stress resistance.

Epigenetic modifications, changes in gene expression that don’t alter the DNA sequence itself, play a crucial role in aging. Epigenetic clocks, which measure biological age based on DNA methylation patterns, can predict mortality risk and age-related diseases more accurately than chronological age.

Emerging interventions aim to modify epigenetic patterns to “reprogram” cells to a younger state. Early studies in animals have shown promise, with researchers able to reverse some aspects of aging through epigenetic reprogramming.

Senolytics and Senomorphics

Cellular senescence, the state of irreversible growth arrest that cells enter in response to damage or stress, is a key hallmark of aging. While senescence prevents damaged cells from becoming cancerous, the accumulation of senescent cells contributes to aging and age-related diseases through the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), a pro-inflammatory secretome that damages surrounding tissues.

Senolytics are compounds that selectively eliminate senescent cells. Early studies in animals have shown that removing senescent cells can improve healthspan, reduce inflammation, delay age-related diseases, and extend lifespan. Several senolytic compounds are currently in human clinical trials.

Senomorphics are agents that suppress the harmful SASP without killing senescent cells. These may offer a complementary approach to senolytics, potentially with fewer side effects.

NAD+ Boosters

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is a coenzyme essential for cellular energy production and DNA repair. NAD+ levels decline significantly with age, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction, reduced cellular repair capacity, and accelerated aging.

NAD+ precursors like nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) can boost NAD+ levels in animal studies, improving mitochondrial function, insulin sensitivity, and cardiovascular health while extending lifespan.

Human studies of NAD+ precursors have shown promising results in improving markers of metabolic health and vascular function, though long-term effects on lifespan and health span are still being investigated.

mTOR Inhibitors

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a central regulator of cell growth, proliferation, and metabolism. Overactivation of mTOR signaling accelerates aging, while inhibition extends lifespan in multiple species.

Rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, is the most robust pharmacological lifespan-extending intervention discovered to date in animal studies. It extends lifespan even when started late in life and improves multiple health parameters.

While rapamycin has immunosuppressive effects that limit its use as a general anti-aging drug, researchers are developing rapalogs, derivatives of rapamycin with fewer side effects, and exploring intermittent dosing regimens that may provide benefits without significant adverse effects.

Metformin and Other Diabetes Drugs

Metformin, a widely prescribed drug for type 2 diabetes, has shown promise as a potential anti-aging intervention. It activates AMPK, a cellular energy sensor that influences multiple longevity pathways.

Epidemiological studies have found that diabetics taking metformin have lower mortality rates than non-diabetics not taking the drug, suggesting potential benefits beyond diabetes management. The TAME (Targeting Aging with Metformin) trial is currently underway to evaluate metformin’s effects on aging in non-diabetics.

Other diabetes drugs like acarbose and SGLT2 inhibitors have also shown lifespan-extending effects in animal studies and are being investigated for their potential anti-aging properties.

Stem Cell Therapies and Regenerative Medicine

Stem cell exhaustion, the decline in the body’s ability to repair and regenerate tissues, is a key hallmark of aging. Stem cell therapies aim to restore this regenerative capacity by introducing new stem cells or stimulating existing ones.

Early research has shown promise in using stem cells to treat age-related conditions like osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders. While most applications are still experimental, the field is advancing rapidly.

Regenerative medicine approaches like tissue engineering and 3D bioprinting may eventually allow for the replacement of damaged tissues and organs, potentially transforming the treatment of age-related diseases.

Mitochondrial Therapies

Mitochondria, the cellular powerhouses responsible for energy production, decline in function with age, contributing to fatigue, metabolic dysfunction, and accelerated aging. Mitochondrial therapies aim to restore mitochondrial function and biogenesis.

Approaches include mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants like MitoQ, compounds that stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis like NAD+ boosters, and mitochondrial transplantation, where healthy mitochondria are transferred to damaged cells.

While still in early stages, mitochondrial therapies represent a promising approach to addressing a fundamental aspect of aging at the cellular level.

Artificial Intelligence in Longevity Research

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are transforming longevity research by enabling the analysis of vast amounts of data to identify patterns and interventions that might otherwise go unnoticed.

AI is being used to develop more accurate biomarkers of aging, predict individual responses to interventions, identify novel drug targets, and personalize longevity recommendations based on individual health data.

As AI capabilities continue to advance, they may accelerate the pace of discovery in longevity science and enable more precise, personalized approaches to extending health span and lifespan.

The Future of Longevity Medicine

The field of longevity medicine is evolving rapidly, with the potential to transform healthcare from a disease-focused model to one that proactively addresses aging itself. Future approaches may include:

Personalized longevity plans based on individual genetic, epigenetic, and biomarker profiles, with interventions tailored to specific aging mechanisms.

Regular monitoring of biological age using advanced biomarkers and epigenetic clocks, allowing for early intervention when aging processes accelerate.

Combination therapies that target multiple aging pathways simultaneously, potentially providing synergistic benefits beyond single interventions.

Preventive protocols that begin early in life, addressing aging processes before significant damage occurs, rather than treating diseases after they manifest.

As these approaches develop, ethical considerations around access, equity, and societal implications will need to be carefully addressed to ensure that the benefits of longevity science are available to all.

Practical Implementation and Integration

Understanding the various factors that influence longevity is only the first step; implementing and integrating these practices into daily life is where the real benefits are realized. This section provides practical guidance for creating a personalized longevity plan that addresses nutrition, physical activity, sleep, stress management, social connection, and environmental factors in a sustainable way.

Creating a Personalized Longevity Plan

A personalized longevity plan should be tailored to individual needs, preferences, health status, and resources. It should address multiple dimensions of health while being realistic and sustainable over the long term.

The first step in creating a personalized plan is assessment. This might include:

Health evaluations with healthcare providers, including blood tests, physical examinations, and screenings for age-related conditions.

Assessment of current lifestyle habits, including diet, physical activity, sleep patterns, stress levels, and social connections.

Consideration of personal health history, genetic factors, and family history of age-related diseases.

Identification of personal values, priorities, and goals for health and longevity.

Based on this assessment, specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals can be developed for each area of focus. For example, a nutrition goal might be to increase vegetable intake to five servings per day within a month, or a physical activity goal might be to gradually increase walking to 10,000 steps daily over three months.

Starting Small and Building Momentum

Attempting to change too many aspects of lifestyle simultaneously can be overwhelming and lead to burnout. A more effective approach is to start with small, manageable changes and build momentum over time.

The concept of “keystone habits” can be useful here—small changes that naturally lead to other positive behaviors. For example, establishing a morning walking routine might naturally lead to better sleep, improved dietary choices, and increased social interaction.

Focusing on one or two areas at a time allows for greater attention and energy to be directed toward establishing new habits before moving on to additional changes. As each new habit becomes automatic, it becomes part of a foundation of healthy behaviors that support longevity.

Tracking Progress and Adjusting

Regular monitoring of progress helps maintain motivation and allows for adjustments to the plan as needed. Tracking methods might include:

Physical measurements like weight, body composition, blood pressure, and resting heart rate.

Biological markers from blood tests, including inflammation markers, lipid profiles, glucose metabolism, and emerging aging biomarkers.

Functional assessments like fitness tests, cognitive evaluations, and measures of daily functioning.

Subjective measures like energy levels, mood, sleep quality, and overall well-being.

Based on these assessments, the longevity plan can be refined and adjusted over time. What works initially may need modification as circumstances change, health status evolves, or new scientific evidence emerges.

Overcoming Barriers and Obstacles

Implementing lifestyle changes inevitably encounters barriers and obstacles. Anticipating these challenges and developing strategies to address them can improve long-term adherence.

Common barriers include:

Time constraints in busy schedules can be addressed by integrating activities into existing routines, breaking exercise into shorter sessions, or waking earlier to allow time for healthy habits.

Financial limitations might require prioritizing low-cost interventions like walking, home-based exercise, and seasonal produce, or focusing on changes that provide the most value for money.

Social influences can be managed by communicating health goals to friends and family, seeking support from like-minded individuals, or finding social activities that align with health objectives.

Motivation fluctuations are normal and can be addressed by focusing on intrinsic motivations, celebrating small victories, and reconnecting with the deeper reasons for pursuing longevity.

Lack of knowledge or skills can be overcome through education, working with professionals like nutritionists or trainers, or joining community programs that provide guidance and support.

Building a Support System

Social support is crucial for maintaining long-term lifestyle changes. Building a network of supportive individuals and resources can provide encouragement, accountability, and practical assistance.

Potential sources of support include:

Healthcare providers who understand and support longevity-focused approaches to health.

Family and friends who encourage healthy behaviors and may participate in activities together.

Community groups or classes focused on healthy cooking, physical activity, or other relevant interests.

Online communities and forums where individuals share experiences, challenges, and successes related to longevity practices.

Professionals like nutritionists, personal trainers, therapists, or health coaches who provide expert guidance and accountability.

Technology and Tools for Longevity

Numerous technologies and tools can support longevity efforts by providing information, tracking progress, and offering guidance. These include:

Wearable devices that monitor physical activity, sleep, heart rate, and other physiological parameters.

Smartphone apps for tracking nutrition, exercise, meditation, and other health-related activities.

Home monitoring devices for blood pressure, blood glucose, and other health metrics.

Online platforms that provide personalized recommendations based on health data and goals.

Telehealth services that connect individuals with healthcare providers and specialists remotely.

While technology can be valuable, it’s important to use it as a tool rather than becoming overly dependent on it. The focus should remain on the behaviors and outcomes rather than the data itself.

Integrating Longevity Practices into Daily Life

For longevity practices to be sustainable, they need to be integrated seamlessly into daily life rather than feeling like additional burdens. This integration might involve:

Designing living spaces that encourage healthy behaviors, like having exercise equipment readily available, keeping healthy foods visible and accessible, and creating a sleep-conducive bedroom environment.

Establishing routines that incorporate multiple health-promoting behaviors, such as a morning routine that includes physical activity, meditation, and a healthy breakfast.

Combining social connection with physical activity through walking groups, sports teams, or active hobbies with friends.

Aligning daily schedules with circadian rhythms by exposing oneself to natural light in the morning, limiting artificial light at night, and maintaining consistent sleep and meal times.

Finding enjoyment in healthy practices by choosing forms of exercise that are pleasurable, experimenting with nutritious foods that taste good, and engaging in stress-reducing activities that are inherently rewarding.

Adapting to Different Life Stages

Longevity practices need to be adapted to different life stages and circumstances. What works for a young adult may not be appropriate for an older adult, and life transitions like career changes, parenthood, or retirement may require adjustments to the longevity plan.

Key considerations for different life stages include:

Young adulthood is an ideal time to establish healthy habits that can prevent accelerated aging later in life. Focus might include building fitness, establishing healthy eating patterns, developing stress management skills, and building social connections.

Midlife often brings increased responsibilities and time constraints, making efficiency important. Focus might include maintaining physical activity, managing stress, prioritizing sleep, and regular health monitoring to detect early signs of age-related changes.

Older adulthood requires attention to maintaining muscle mass, bone density, cognitive function, and social engagement. Physical activity may need to be modified to accommodate changing abilities, while nutrition may need to be adjusted to account for changing metabolic needs.

Adapting longevity practices to life stages ensures that they remain relevant, appropriate, and sustainable throughout the lifespan.

The Importance of Flexibility and Self-Compassion

Perfection is not required or realistic when implementing longevity practices. Flexibility and self-compassion are essential for long-term adherence and overall well-being.

Occasional deviations from the plan are normal and should be viewed as part of the journey rather than failures. The key is to return to healthy practices without guilt or self-criticism.

Circumstances change, and what works at one time may not work at another. Being willing to adjust the plan based on changing needs, preferences, and circumstances is more important than rigid adherence to a specific approach.

Self-compassion involves treating oneself with the same kindness and understanding that would be offered to a friend. This mindset supports resilience, motivation, and overall psychological well-being, all of which contribute to longevity.

Conclusion

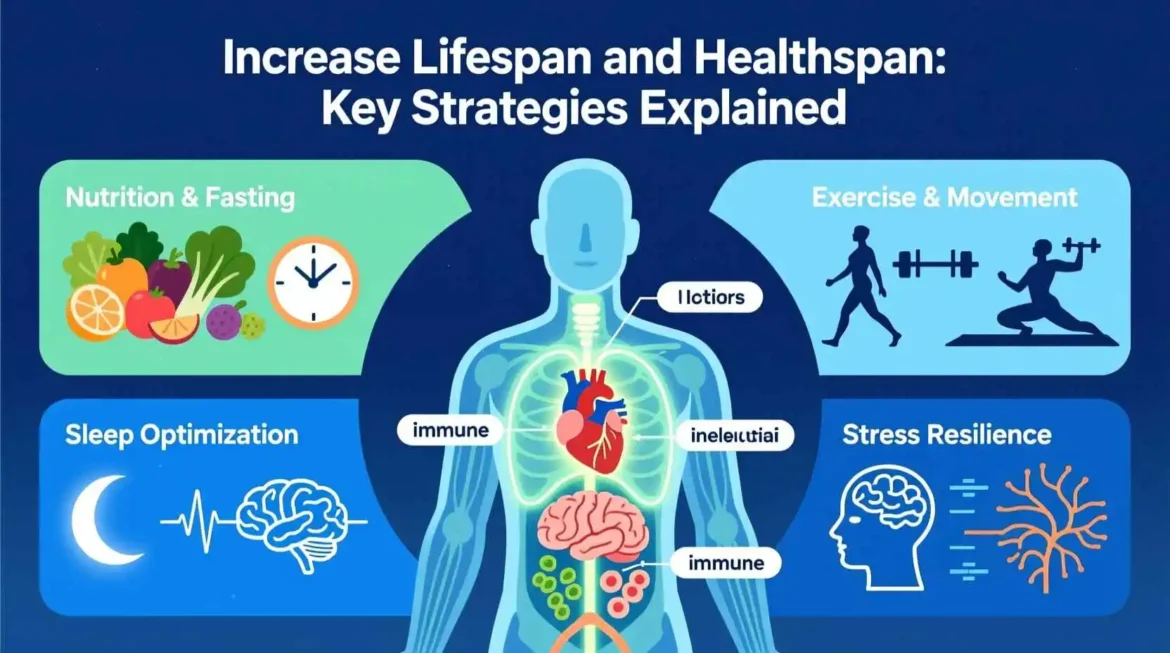

The pursuit of increased lifespan and health span is a multifaceted journey that encompasses nutrition, physical activity, sleep, stress management, social connection, environmental factors, and emerging scientific interventions. By understanding the complex interplay of these factors and implementing evidence-based strategies tailored to individual needs and circumstances, we can significantly influence how we age.

The field of longevity science is advancing rapidly, offering new insights and interventions that may transform our approach to aging in the coming decades. However, the foundational elements of healthy aging remain accessible to everyone through lifestyle practices that have stood the test of time and scientific scrutiny.

Ultimately, the goal of extending health span is not merely to add years to life but to add life to years. By prioritizing health, well-being, and vitality throughout the lifespan, we can increase not only how long we live but how well we live, enjoying greater independence, purpose, and fulfillment in our later years.

The journey toward optimal longevity is personal and ongoing, requiring commitment, adaptation, and self-compassion. By embracing this journey with curiosity and persistence, we can unlock the potential for a longer, healthier, and more vibrant life.

FAQs

- What is the difference between lifespan and health span?

Lifespan refers to the total number of years a person lives, while healthspan encompasses the years of life spent in good health, free from chronic diseases and disabilities. The goal of longevity medicine is to extend both, but particularly health span, ensuring that additional years are lived with vitality and quality of life.

- Can genetics determine how long I will live?

Genetics play a role in longevity, accounting for approximately 20-30% of lifespan variation. However, lifestyle and environmental factors have a more significant impact. Even with genetic predispositions to certain conditions, healthy lifestyle choices can substantially influence both lifespan and health span.

- What is the most effective diet for longevity?

Research suggests that predominantly plant-based diets, rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, are associated with exceptional longevity. The Mediterranean diet and traditional Okinawan diet are examples of eating patterns linked to increased lifespan and health span. Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting also show promise for extending longevity.

- How much exercise do I need for optimal longevity?

The World Health Organization recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity per week, combined with muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days per week. However, any amount of physical activity is beneficial, and more activity generally provides greater benefits up to a point.

- Is intermittent fasting effective for extending lifespan?

Intermittent fasting has shown promise in animal studies for extending lifespan and improving health markers. Human studies suggest benefits for metabolic health, inflammation, and cellular repair processes like autophagy. While more research is needed, intermittent fasting appears to be a promising approach for enhancing health span and potentially lifespan.

- How does sleep affect aging?

Quality sleep is essential for cellular repair, cognitive function, immune health, and metabolic regulation. Chronic sleep deprivation accelerates aging processes, increases inflammation, and raises the risk of numerous age-related diseases. Most adults need 7-8 hours of quality sleep per night for optimal health and longevity.

- Can stress really shorten my life?

Chronic stress accelerates aging at the cellular level, shortening telomeres and promoting epigenetic aging. It also contributes to inflammation, immune dysfunction, and unhealthy behaviors that increase the risk of age-related diseases. Effective stress management is crucial for both lifespan and health span.

- What role do social connections play in longevity?

Strong social connections are consistently associated with increased longevity and better health outcomes. Social isolation and loneliness are significant risk factors for premature mortality, comparable to well-established risk factors like smoking and obesity. Meaningful relationships provide emotional support, reduce stress, and encourage healthy behaviors.

- How does the environment impact aging?

Environmental factors like air quality, water quality, exposure to toxins, noise pollution, and access to green spaces can significantly influence aging processes. Minimizing exposure to environmental toxins and maximizing contact with natural environments can support longevity.

- What are senolytics and how do they work?

Senolytics are compounds that selectively eliminate senescent cells, which accumulate with age and contribute to inflammation and tissue damage. By removing these cells, senolytics aim to reduce inflammation, improve tissue function, and potentially extend healthspan and lifespan. Several senolytic compounds are currently in human clinical trials.

- Can supplements help me live longer?

While some supplements like vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids, and NAD+ precursors show promise for supporting health and potentially extending longevity, most supplements have limited evidence for significant lifespan extension in humans. A nutrient-dense diet should be the foundation, with supplements used strategically to address specific deficiencies or support particular health goals.

- How important is maintaining a healthy weight for longevity?

Maintaining a healthy weight is important for longevity, as obesity is associated with increased risk of numerous age-related diseases and premature mortality. However, the relationship between weight and longevity is complex, with factors like body composition, metabolic health, and weight history also playing important roles.

- What is the role of inflammation in aging?

Chronic low-grade inflammation, often called “inflammaging,” is a key driver of aging and age-related diseases. It contributes to cellular damage, tissue dysfunction, and the development of conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders. Anti-inflammatory lifestyle practices can help mitigate this process.

- How does alcohol consumption affect longevity?

Moderate alcohol consumption, particularly red wine, has been associated with certain health benefits in some studies. However, excessive alcohol consumption is clearly detrimental to health and longevity. Current guidelines suggest that if you drink, doing so in moderation is best, and abstaining is also a healthy choice.

- Can I reverse aging or just slow it down?

While completely reversing aging is not currently possible, research suggests that certain interventions may slow or partially reverse some aspects of aging at the cellular level. Lifestyle interventions like diet, exercise, and stress management can improve health markers and functional status, effectively making some biological systems “younger.”

- What are telomeres and how do they relate to aging?

Telomeres are protective caps at the ends of chromosomes that shorten with each cell division. When telomeres become critically short, cells enter senescence or die. Telomere length is considered a biomarker of biological aging, and shorter telomeres are associated with increased risk of age-related diseases and mortality.

- How does mitochondrial function affect aging?

Mitochondria are the cellular powerhouses responsible for energy production. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of aging, contributing to fatigue, metabolic decline, and cellular damage. Interventions that support mitochondrial health, like exercise and certain supplements, may help slow aging processes.

- What is the role of autophagy in longevity?

Autophagy is a cellular cleaning process that removes damaged components and recycles them for energy or building blocks. This process declines with age, contributing to the accumulation of cellular damage. Interventions like fasting, exercise, and certain compounds can stimulate autophagy, potentially extending health span and lifespan.

- Can meditation really help me live longer?

Regular meditation practice has been shown to reduce stress, lower inflammation, improve immune function, and even slow cellular aging by increasing telomerase activity. These effects may contribute to increased longevity and better health outcomes, particularly when combined with other healthy lifestyle practices.

- How does hydration affect aging?

Proper hydration is essential for cellular function, detoxification, and overall health. Chronic dehydration can impair cognitive function, physical performance, and metabolic health, potentially accelerating aging processes. Maintaining adequate hydration is a simple but important aspect of longevity.

- What are epigenetic clocks and how do they measure aging?

Epigenetic clocks are biomarkers that measure biological age based on DNA methylation patterns at specific sites in the genome. These clocks can predict mortality risk and age-related diseases more accurately than chronological age, providing a tool to assess the effectiveness of longevity interventions.

- How does gut health influence aging?

The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in immune function, inflammation, nutrient absorption, and even brain health through the gut-brain axis. Changes in gut microbiome composition with age may contribute to aging processes and age-related diseases. Supporting gut health through diet, probiotics, and prebiotics may promote healthy aging.

- Is it ever too late to start improving my health for longevity?

It’s never too late to benefit from healthy lifestyle changes. Research shows that even older adults can experience significant improvements in health markers, functional status, and mortality risk by adopting healthier habits. While starting earlier is ideal, interventions at any age can enhance health span and potentially extend lifespan.

- How does oral health relate to longevity?

Oral health is connected to systemic health through various mechanisms. Poor oral health, particularly periodontal disease, is associated with increased inflammation, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cognitive decline. Maintaining good oral hygiene and regular dental care is an important aspect of overall health and longevity.

- What role does purpose or meaning in life play in longevity?

Having a sense of purpose or meaning in life is associated with reduced stress, better health outcomes, and increased longevity. Purpose may buffer against stress, provide motivation for healthy behaviors, and contribute to psychological resilience, all of which support healthy aging.

- How do hormones affect aging?

Hormonal changes are a normal part of aging, with levels of hormones like growth hormone, DHEA, testosterone, and estrogen typically declining with age. These changes contribute to various aspects of aging, including reduced muscle mass, decreased bone density, and altered metabolism. Hormone replacement therapies may offer benefits for some individuals but require careful consideration of risks and benefits.

- Can learning new things help me live longer?

Lifelong learning and cognitive engagement are associated with better cognitive health, reduced risk of dementia, and potentially increased longevity. Mental stimulation may build cognitive reserve, helping the brain resist damage and maintain function despite aging processes.

- How does exposure to cold or heat affect longevity?

Exposure to mild cold or heat stress, such as through cold showers, sauna use, or temperature variations, may activate beneficial cellular stress response pathways that enhance resilience and potentially extend longevity. Practices like sauna bathing have been associated with reduced cardiovascular mortality and increased lifespan in observational studies.

- What is the role of antioxidants in aging?

Antioxidants neutralize free radicals, reducing oxidative stress that contributes to cellular damage and aging. While antioxidant supplements have shown mixed results in studies, obtaining antioxidants from whole foods like fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds is consistently associated with better health outcomes and potentially increased longevity.

- How can I create a personalized longevity plan?

Creating a personalized longevity plan involves assessing current health status, lifestyle habits, and personal goals; identifying areas for improvement; setting specific, achievable goals; implementing changes gradually; tracking progress; and adjusting the plan as needed. Working with healthcare providers and possibly specialists in nutrition, fitness, or longevity medicine can help develop a plan tailored to individual needs and circumstances.

Medical Disclaimer:

The information provided on this website is for general educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.