Understanding Asymmetrical Shoulders: Causes, Diagnosis, Treatments and Styling Tips

“Shoulder asymmetry is often a subtle clue that the musculoskeletal system is out of balance. Recognizing it early allows us to intervene with targeted therapy before compensations become chronic.” – Dr. Elena Martínez, DPT, Orthopedic Rehabilitation Specialist

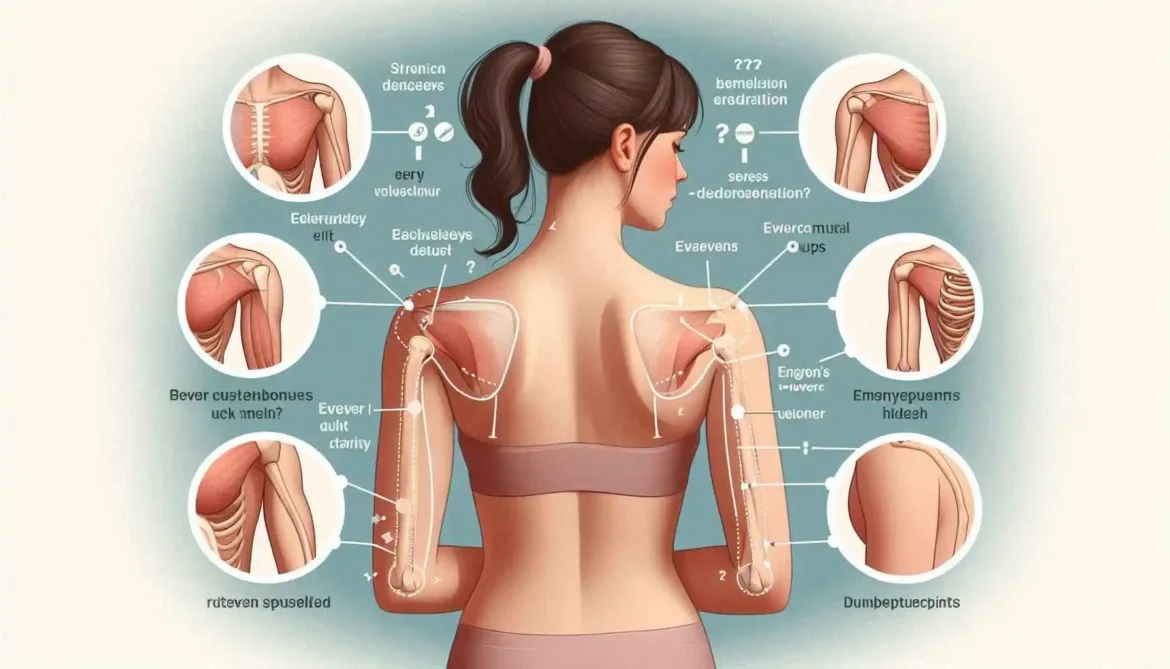

In our daily interactions with patients, athletes, and office workers, we frequently encounter individuals who notice that one shoulder sits higher, looks broader, or feels stiffer than the other. While a perfectly symmetrical torso is the ideal, minor differences are common and usually harmless. However, when the discrepancy becomes pronounced, it can signal underlying issues that merit attention. In this article we will explore the anatomy behind shoulder symmetry, the most common causes of asymmetry, how clinicians diagnose the condition, the spectrum of treatment options, and practical styling advice for anyone who wants to look and feel confident despite the imbalance.

1. Why Shoulder Symmetry Matters

The shoulder girdle is far more than a pair of bones that simply sit on the sides of the torso. It is a highly mobile, inter‑connected kinetic chain that includes the clavicle (collarbone), scapula (shoulder blade), humerus (upper‑arm bone), a network of hundreds of muscles, dozens of ligaments, and a complex web of nerves. Because every movement of the arm—reaching for a high shelf, lifting a grocery bag, or throwing a baseball—relies on this chain working in harmony, even a subtle imbalance between the left and right sides can set off a cascade of problems throughout the body. Below is an in‑depth look at why maintaining shoulder symmetry is essential for function, posture, aesthetics, and long‑term health.

A. Efficient Force Transmission

- Biomechanical Leverage

- The scapula serves as a stable platform for the humerus to rotate around. When the scapula sits level and tilts correctly, the rotator‑cuff muscles can generate force with optimal leverage.

- A deviated scapula (elevated, protracted, or excessively winged) shortens or lengthens the muscle fibers unevenly, reducing the mechanical advantage of the deltoid, supraspinatus, and other prime movers.

- Energy Conservation

- Symmetrical shoulders allow the kinetic energy generated by the legs and core to be transferred smoothly through the torso and into the arm.

- When one shoulder is higher or rotated, the body must recruit extra stabilizers (e.g., the ipsilateral trapezius, levator scapulae, or even the contralateral side) to compensate, which wastes energy and accelerates muscular fatigue.

- Performance in Dynamic Activities

- Reaching: A level shoulder girdle ensures that the hand travels along a straight trajectory, avoiding unnecessary lateral deviation that can strain the elbow or wrist.

- Lifting: Balanced shoulders keep the load centered over the mid‑line of the body, allowing the hips and knees to bear the majority of the weight. An asymmetrical shoulder position shifts the center of mass laterally, forcing the spine to work harder to maintain balance.

- Throwing / Overhead Sports: The “kinetic chain” in a baseball pitch or basketball shot starts at the lower body, moves through the torso, and finishes in the hand. A misaligned shoulder interrupts this chain, reducing ball velocity and increasing the risk of rotator‑cuff overload.

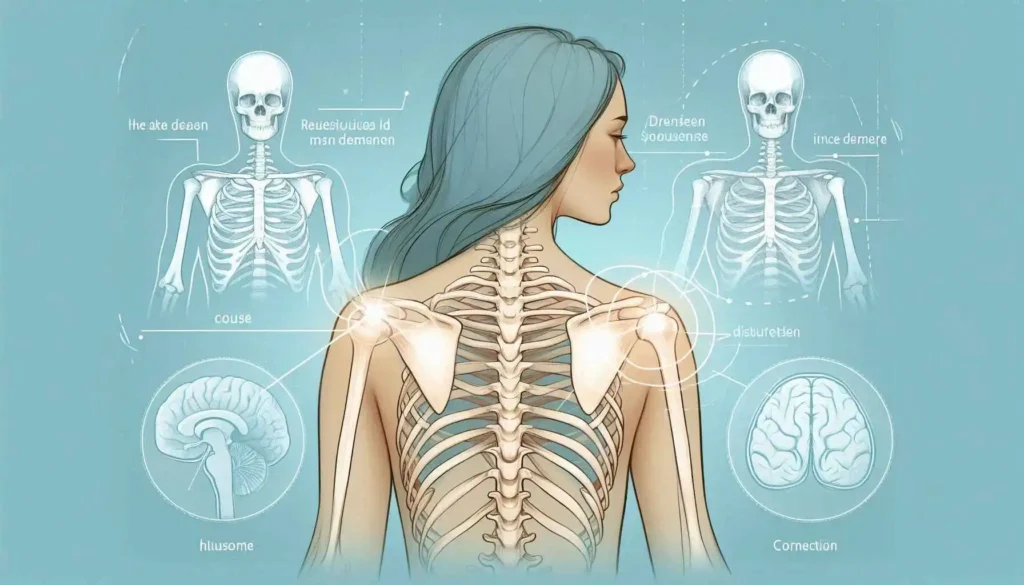

B. Optimal Posture and Spinal Health

- Cervical Spine Alignment

- The clavicle connects directly to the sternum, while the scapula articulates with the cervical vertebrae via the levator scapulae and upper trapezius. A raised shoulder on one side pulls the adjacent cervical vertebrae upward, creating a lateral flexion or rotation of the neck. Over time this can manifest as a “head‑tilt” posture, tension headaches, and even nerve impingement (e.g., C2–C3 radiculopathy).

- Thoracic and Lumbar Compensation

- An uneven shoulder girdle forces the thoracic spine to laterally bend or rotate to maintain a level visual horizon. The lumbar spine then compensates with opposite side bending or rotation, creating a “S‑shaped” curvature that places abnormal shear forces on intervertebral discs.

- Chronic asymmetry can precipitate thoracic outlet syndrome, where the subclavian vessels and brachial plexus become compressed between a high‑riding first rib and an over‑elevated scapula.

- Pelvic Tilt and Hip Mechanics

- The body strives for a balanced center of gravity. When the shoulders are misaligned, the pelvis often tilts to the opposite side, altering hip joint loading patterns. This can lead to hip impingement, altered gait, and even knee valgus or varus stresses.

C. Aesthetic Harmony and Personal Confidence

- Clothing Fit

- Even a 5‑mm difference in shoulder height can be the difference between a shirt lying flat and one pulling at the seam. Tailors and designers consider shoulder symmetry a key “fit metric,” because asymmetry creates visual tension that makes the torso appear crooked or “off‑balance.”

- For athletes and performers whose appearance is part of their brand (e.g., swimmers, dancers, models), a symmetrical shoulder line enhances the perception of strength, poise, and professionalism.

- Self‑Image and Psychological Impact

- Humans are wired to notice visual symmetry; it is often associated with health and attractiveness. Persistent shoulder asymmetry can become a source of self‑consciousness, especially when it is visible in photographs or on video.

- Studies in body‑image psychology have shown that perceived physical asymmetry correlates with lower self‑esteem and higher rates of social anxiety, particularly in adolescents and those in appearance‑focused professions.

D. The Domino Effect of Compensation

When one shoulder deviates, the body instinctively recruits other structures to “make the numbers work.” Below are the most common compensatory patterns and their downstream consequences:

| Primary Deviation | Typical Compensation | Potential Long‑Term Issues |

| Elevated Right Shoulder | Left-side lateral flexion of the spine; activation of left lower trapezius to pull the scapula back | Chronic left‑side thoracic scoliosis, unilateral rib‑cage restriction |

| Protracted Scapula (winged) | Over‑activity of the upper trapezius and levator scapulae to stabilize the shoulder; forward head posture | Cervical disc degeneration, tension‑type headaches |

| Rotated Scapula (internal rotation) | Increased external rotation of the contralateral hip to keep pelvis level | Hip internal‑rotation strain, iliotibial band syndrome |

| Anterior Tilt of One Shoulder | Increased lumbar extension on the opposite side to keep eyes level | Lumbar facet joint overload, sacroiliac joint dysfunction |

| Uneven Clavicle Height | Asymmetrical activation of the serratus anterior and rhomboids; altered breathing mechanics | Reduced rib‑cage expansion, decreased vital capacity |

These compensations are rarely isolated; they intertwine, creating a “chain reaction” that can affect distant joints such as the knees, ankles, and even the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). For example, a persistent pelvis tilt induced by shoulder imbalance may force the knees into continual valgus (knock‑knees), predisposing the individual to patellofemoral pain syndrome.

2. Common Causes of Asymmetrical Shoulders

Below is a concise table that categorizes the most frequent origins of shoulder asymmetry, the typical presentation, and the primary red‑flag signs that warrant prompt medical evaluation.

| Category | Typical Etiology | Key Clinical Features | Red‑Flag Signs |

| Postural | Prolonged slouching, desk‑bound work, dominant‑hand bias | One shoulder appears higher, rounded upper back on the opposite side | Persistent neck or arm pain > 6 weeks, neurological deficits |

| Muscular Imbalance | Over‑development of pectoralis major/minor, weak trapezius/serratus anterior | Uneven shoulder blade (scapular) positioning, limited external rotation | Sudden loss of strength, visible muscle wasting |

| Scoliosis / Spinal Curvature | Lateral curvature of thoracic spine (idiopathic or congenital) | Shoulder elevation correlates with curve apex, rib hump | Progressive curvature, breathing difficulty |

| Congenital Anomalies | Klippel‑Feil syndrome, Sprengel’s deformity | High‑set scapula, limited neck motion | Associated cardiac or respiratory anomalies |

| Trauma / Fracture | Clavicle fracture, scapular fracture, dislocation | Acute pain, swelling, visible deformity | Open wound, neurovascular compromise |

| Neurological | Brachial plexus injury, spinal accessory nerve palsy | Weakness in serratus or trapezius, winging scapula | Rapid onset weakness, loss of sensation |

| Degenerative Joint Disease | Osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint | Localized AC joint tenderness, crepitus, reduced ROM | Night pain, systemic inflammatory signs |

Note: The table is meant for educational purposes only; a thorough clinical evaluation is essential for accurate diagnosis.

3. How Clinicians Diagnose Shoulder Asymmetry

Diagnosing the underlying cause of shoulder asymmetry is rarely a “one‑size‑fits‑all” process. It requires a methodical, layered assessment that weaves together the patient’s story, a focused physical examination, and, when indicated, targeted imaging studies. By moving from the broad (general history) to the specific (objective findings), the clinician can pinpoint whether the asymmetry stems from a postural habit, a structural lesion, a neuromuscular imbalance, or a combination of factors.

3.1 Structured History

A thorough history is the foundation of any musculoskeletal diagnosis. It not only provides clues about the timing and mechanism of the asymmetry, but also uncovers red‑flag signs, previous treatments, and psychosocial contributors that may influence both presentation and outcome.

| Domain | Key Questions | Why It Matters |

| Onset & Progression | • When did you first notice the shoulder looking different? • Was the change abrupt (e.g., after a fall) or insidious (evolving over weeks/months)? • Has the asymmetry worsened, plateaued, or fluctuated? | Sudden onset often points to traumatic injury (fracture, dislocation, rotator‑cuff tear). Gradual development suggests postural adaptations, muscular imbalance, or degenerative changes. |

| Activity Profile | • What are your primary occupations or hobbies? (e.g., pitcher, carpenter, computer programmer, weight‑lifter) • How many hours per day do you spend in overhead or repetitive motions? • Do you have a regular training regimen? | Identifies repetitive‑use disorders (e.g., internal rotation stress in pitchers) and informs load‑related pathology such as over‑use rotator‑cuff tendinopathy or scapular dyskinesis. |

| Pain Characteristics | • Where is the pain located (anterior, lateral, posterior, deep vs. superficial)? • Rate intensity on a 0‑10 scale (rest, activity, night). • What makes it better or worse (elevating the arm, resting, NSAIDs, heat, cold)? | Pain pattern helps differentiate intra‑articular (e.g., glenohumeral arthritis, labral tear) from extra‑articular (e.g., bursitis, muscular strain) sources. Night pain may signal rotator‑cuff pathology or cervical radiculopathy. |

| Neurological Symptoms | • Do you experience numbness, tingling, or “pins‑and‑needles” in the arm, hand, or fingers? • Have you noticed any weakness when gripping, lifting, or performing specific tasks? • Is there a sense of “dropping” objects? | Suggests cervical radiculopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome, or brachial plexus involvement—all of which can manifest as shoulder asymmetry due to altered muscular recruitment. |

| Previous Interventions | • Have you tried physical therapy, chiropractic adjustments, acupuncture, or injections? • What surgeries (if any) have you undergone on the shoulder, neck, or spine? • What was the outcome of each intervention? | Determines treatment responsiveness and may uncover iatrogenic contributors (e.g., post‑operative stiffness) or chronicity that influences prognosis. |

| Medical & Psychosocial Context | • Do you have systemic conditions (diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disease) that affect connective tissue? • Any recent infections, fevers, or weight loss? • How does the shoulder asymmetry affect work, sleep, recreation, or mood? | Systemic illnesses can produce secondary musculoskeletal changes (e.g., frozen shoulder in diabetes). Psychosocial stressors may amplify pain perception and limit rehabilitation adherence. |

Tip for Clinicians: Document the history in a timeline format (e.g., “12 months ago → onset after starting weight‑lifting program → 3 months later → gradual worsening”) to visualize the trajectory and pinpoint critical events.

3.2 Physical Examination

A systematic examination builds on the history by providing objective data that can confirm or refute suspected diagnoses. The exam can be divided into inspection, palpation, range‑of‑motion (ROM) testing, strength testing, scapular assessment, and special orthopedic tests.

3.2.1 Inspection

- Postural Overview – Observe the patient from the front, back, and side while standing relaxed.

- Look for shoulder height difference (≥1 cm is often clinically significant).

- Note scapular winging, protraction/retraction, downward/upward rotation, and thoracic kyphosis.

- Dynamic Observation – Ask the patient to perform functional tasks (e.g., reach overhead, lift a light object).

- Watch for compensatory trunk lean, early scapular elevation, or asymmetric scapulothoracic motion.

- Skin & Soft‑Tissue Changes – Look for redness, bruising, atrophy, or hypertrophy of the deltoid and periscapular muscles.

3.2.2 Palpation

| Structure | Palpation Points | Findings to Note |

| Clavicle & AC joint | Distal clavicle, AC joint line | Tenderness → possible AC arthropathy or clavicular fracture |

| Acromion & Subacromial space | Lateral acromion, beneath deltoid | Pain on palpation → subacromial bursitis or rotator‑cuff impingement |

| Coracoid process | Anterior to the shoulder | Tenderness may suggest coracoid impingement or biceps tendon pathology |

| Glenohumeral joint line | Anterior and posterior joint recess | Crepitus or joint line tenderness → arthritis, labral tear |

| Muscle bellies | Deltoid (anterior, middle, posterior), supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis | Muscle atrophy (e.g., supraspinatus) indicates chronic rotator‑cuff pathology; hypertonicity may point to compensatory overuse |

3.2.3 Range‑of‑Motion (Active & Passive)

| Motion | Normal Range | Abnormal Findings | Clinical Implication |

| Flexion | 0‑180° | Limited early, pain at 90° → impingement; loss beyond 150° → capsular tightness | Helps differentiate intra‑ vs. extra‑articular restriction |

| Abduction | 0‑180° | “Stop‑sign” at 90° → subacromial impingement; painful arc (60‑120°) → classic impingement pattern | |

| External Rotation (ER) | 0‑90° (at side) | Reduced ER with the arm at 0° indicates posterior capsular tightness; limited ER at 90° of abduction suggests rotator‑cuff tear | |

| Internal Rotation (IR) | Reaches behind the back (T7–T9) | Severely limited IR → posterior shoulder contracture or glenohumeral arthritis | |

| Cross‑Body Adduction | 0‑50° | Pain or block → acromioclavicular joint pathology |

Tip: Use a goniometer for quantitative measurement; document both active and passive ROM to distinguish pain‑limited motion from true capsular restriction.

3.2.4 Strength Testing

- Manual Muscle Testing (MMT) – Grade 0–5 for each rotator‑cuff muscle and deltoid.

- Supraspinatus (Jobe test): 90° abduction, resisted upward rotation.

- Infraspinatus/teres minor (External rotation test): 0° adduction, resisted ER.

- Subscapularis (Belly‑press or lift‑off test): 0° adduction, resisted internal rotation.

- Isometric/Isokinetic Dynamometry (if available) – Provides objective torque values for comparison with the contralateral side.

Interpretation: A strength deficit >15% compared with the opposite limb suggests muscle tear, inhibition, or neurological involvement.

3.2.5 Scapular Assessment

| Assessment | How to Perform | Positive Finding | Clinical Relevance |

| Scapular Dyskinesis Test | Patient performs 3 repetitions of 90° forward flexion/abduction while the examiner watches scapular motion. | Winged or early elevation of the scapula | Indicates periscapular muscle imbalance (e.g., serratus anterior weakness) that can produce or exacerbate shoulder asymmetry |

| Wall Slide Test | Patient stands with back against wall, elbows flexed 90°, slides arms upward. | Inability to achieve full overhead contact | Reflects posterior capsule tightness or pectoralis minor shortening |

| Scapular Retraction/Protraction Test | Palpate medial border while patient actively protracts and retracts. | Pain or limited motion | Suggests trapezius or rhomboid dysfunction |

3.2.6 Special Orthopedic Tests