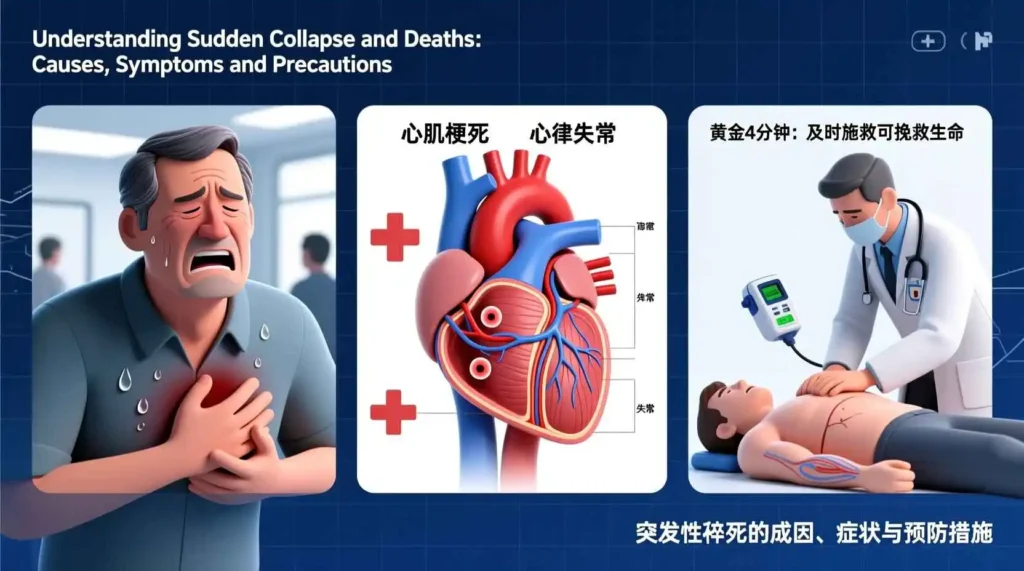

Understanding Sudden Collapse and Deaths: Causes, Symptoms and Precautions

Introduction

Sudden collapse and unexpected deaths represent some of the most alarming and mystifying events in human experience. These incidents strike without warning, leaving families, communities, and medical professionals grappling with profound questions and often searching for answers that may never fully materialize. The sudden transition from apparent health to crisis or death challenges our understanding of human physiology and highlights the fragility of life.

In medical terms, sudden collapse refers to an abrupt loss of consciousness and postural tone, often accompanied by an inability to maintain upright posture without support. This phenomenon can result from numerous underlying causes, ranging from relatively benign conditions like vasovagal syncope to life-threatening emergencies such as cardiac arrhythmias or massive pulmonary embolism. When these events prove fatal, they are classified as sudden deaths, which the World Health Organization defines as deaths occurring within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, though many medical specialties use even shorter time frames, such as death within one hour of symptom onset for sudden cardiac death.

The incidence of sudden collapse and death varies significantly across populations, influenced by factors such as age, underlying health conditions, lifestyle choices, and genetic predisposition. According to global health statistics, sudden cardiac death alone accounts for approximately 15-20% of all deaths worldwide, affecting an estimated 7 million people annually. When other causes of sudden collapse and death are included, these numbers rise substantially, making this a significant public health concern that affects millions of lives each year.

The psychological impact of sudden collapse and death extends far beyond the individual victim. Family members, witnesses, and even emergency responders may experience significant emotional trauma, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression. The unexpected nature of these events denies loved ones the opportunity for preparation or farewell, complicating the grieving process and potentially leading to prolonged psychological distress.

This comprehensive exploration of sudden collapse and death aims to demystify these events by examining their underlying mechanisms, common causes, warning signs, and preventive strategies. By understanding the physiological processes that lead to sudden collapse and the factors that increase risk, we can work toward better prevention, more effective emergency response, and improved outcomes for those affected by these devastating events.

The Physiology of Sudden Collapse

To comprehend sudden collapse, we must first understand the normal physiological mechanisms that maintain consciousness and upright posture. Consciousness depends on adequate blood flow to the brain, specifically to the reticular activating system in the brainstem. The brain, while comprising only about 2% of body weight, consumes approximately 20% of the body’s oxygen and glucose, making it exquisitely sensitive to interruptions in blood supply.

Under normal conditions, the brain maintains adequate perfusion through a complex interplay of cardiac output, vascular tone, and autonomic regulation. The autonomic nervous system continuously monitors and adjusts blood pressure and heart rate to ensure consistent cerebral blood flow regardless of body position. When we stand up, for instance, baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch detect the slight drop in blood pressure and trigger compensatory mechanisms that maintain cerebral perfusion.

Sudden collapse occurs when this delicate balance is disrupted, leading to inadequate cerebral blood flow and loss of consciousness. This disruption can result from three primary mechanisms: decreased cardiac output, vasodilation causing blood pooling in the periphery, or obstruction of blood flow. Each mechanism triggers a cascade of physiological events that ultimately manifest as collapse.

The sequence of events during a typical collapse begins with the inciting incident that disrupts normal circulation. This could be an arrhythmia that reduces cardiac output, a vasovagal response that causes sudden vasodilation, or an obstruction that prevents blood flow. As cerebral perfusion drops, the brain experiences hypoxia and ischemia, leading to dysfunction of the reticular activating system and loss of consciousness.

With the loss of consciousness, postural tone fails, causing the person to fall. This horizontal position often improves cerebral blood flow by eliminating the effects of gravity, which may explain why many individuals regain consciousness relatively quickly after a vasovagal faint. However, in cases where the underlying cause persists, such as ongoing arrhythmia or massive pulmonary embolism, consciousness may not be restored without medical intervention.

The body’s response to collapse involves several compensatory mechanisms. The autonomic nervous system attempts to restore blood pressure and heart rate through increased sympathetic activity. Hormonal responses, including the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine, work to support cardiovascular function. If these compensatory mechanisms succeed, consciousness may be restored; if not, the situation may progress to more severe outcomes, including death.

Understanding the physiology of sudden collapse provides the foundation for recognizing different types of collapse and their potential causes. It also explains why certain positions, such as lying flat, can be beneficial during a collapse and why rapid assessment of circulation, breathing, and consciousness forms the basis of emergency response to these events.

Common Causes of Sudden Collapse

Sudden collapse can result from numerous underlying conditions, ranging from relatively benign to immediately life-threatening. Understanding these causes is essential for appropriate assessment, management, and prevention. The following sections explore the most common causes of sudden collapse, organized by physiological system.

Cardiovascular Causes

Cardiovascular conditions represent the most common causes of sudden collapse, particularly when the event results in death. These conditions directly affect the heart or blood vessels, compromising their ability to maintain adequate blood flow to the brain.

Cardiac arrhythmias top the list of cardiovascular causes. Ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation are particularly dangerous, causing the heart to beat chaotically and ineffectively, leading to a dramatic drop in cardiac output. Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response can also cause collapse, especially in individuals with underlying structural heart disease. Bradyarrhythmias, including complete heart block and sick sinus syndrome, may cause collapse when the heart rate becomes too slow to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion.

Structural heart abnormalities frequently lead to sudden collapse. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition characterized by abnormal thickening of the heart muscle, can obstruct blood flow during exertion and predispose to fatal arrhythmias. This condition represents a leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes. Other structural causes include severe aortic stenosis, which limits blood flow from the heart, and acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), which damages heart muscle and can trigger fatal arrhythmias.

Pulmonary embolism, the obstruction of pulmonary arteries by blood clots, typically originating from deep veins in the legs, can cause sudden collapse when massive. The obstruction increases pressure in the right side of the heart, reducing cardiac output and leading to inadequate cerebral perfusion. Risk factors for pulmonary embolism include prolonged immobility, recent surgery, cancer, and genetic predisposition to clotting.

Aortic dissection, a tear in the inner layer of the aorta, can cause sudden collapse when it leads to rapid blood loss, cardiac tamponade (blood filling the sac around the heart), or obstruction of blood flow to the brain or other vital organs. This condition often presents with severe chest or back pain in addition to collapse.

Neurological Causes

Neurological conditions account for a significant proportion of sudden collapse cases, particularly when the collapse results from disruption of normal brain function or autonomic regulation.

Vasovagal syncope represents one of the most common causes of fainting episodes. This condition results from an exaggerated reflex that causes sudden vasodilation and bradycardia (slow heart rate), leading to a drop in blood pressure and reduced cerebral blood flow. Triggers for vasovagal syncope include emotional distress, the sight of blood, prolonged standing, heat exposure, and pain. While generally benign, vasovagal syncope can cause injury from falls and may be difficult to distinguish from more serious conditions.

Seizures can cause sudden collapse when they involve loss of consciousness and postural control. Epileptic seizures result from abnormal electrical activity in the brain and may be accompanied by convulsions, though absence seizures and some complex partial seizures may cause collapse without convulsive movements. Non-epileptic seizures, related to psychological factors rather than abnormal brain electrical activity, can also lead to collapse.

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) and strokes can cause sudden collapse when they affect areas of the brain responsible for consciousness or motor control. While strokes typically cause additional neurological symptoms such as weakness, numbness, or speech difficulties, some may present primarily with collapse, particularly when they affect the brainstem or cerebellum.

Intracranial hemorrhage, including subarachnoid hemorrhage and intracerebral hemorrhage, can cause sudden collapse due to increased intracranial pressure, direct brain injury, or disruption of autonomic centers. Subarachnoid hemorrhage, often caused by ruptured aneurysms, typically presents with a sudden severe headache in addition to collapse.

Metabolic Causes

Metabolic disturbances can disrupt normal brain function and lead to sudden collapse, particularly when they develop rapidly or reach severe levels.

Hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, represents a common metabolic cause of collapse, particularly in individuals with diabetes treated with insulin or certain oral medications. The brain depends on glucose as its primary energy source, and when blood glucose drops too low, brain function deteriorates, leading to confusion, loss of consciousness, and eventually seizures if untreated. Symptoms often include sweating, tremor, and hunger before collapse, though these warning signs may be blunted in individuals with long-standing diabetes.

Electrolyte abnormalities can cause sudden collapse when they significantly affect cardiac or neurological function. Severe hyponatremia (low sodium levels) can lead to cerebral edema and neurological dysfunction, while hyperkalemia (high potassium levels) can cause fatal cardiac arrhythmias. Other electrolyte disturbances, including hypocalcemia, hypercalcemia, and hypomagnesemia, may also contribute to collapse in severe cases.

Acid-base disorders, including severe metabolic acidosis or alkalosis, can disrupt normal cellular function and lead to collapse. Diabetic ketoacidosis, a complication of diabetes characterized by high blood glucose, ketones, and acidosis, can progress to altered mental status and collapse if untreated.

Respiratory Causes

Conditions that impair oxygenation or ventilation can lead to sudden collapse through cerebral hypoxia. These respiratory causes range from acute airway obstruction to chronic lung diseases with acute exacerbations.

Pulmonary embolism, mentioned earlier as a cardiovascular cause, also functions as a respiratory cause of collapse by impairing gas exchange in the lungs. Large emboli can cause significant ventilation-perfusion mismatch, leading to hypoxemia and inadequate oxygen delivery to the brain.

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can cause collapse during severe exacerbations when airway obstruction leads to significant hypoxemia and hypercapnia (elevated carbon dioxide levels). These conditions typically develop gradually but may progress rapidly in some cases.

Pneumothorax, the presence of air in the pleural space causing lung collapse, can lead to sudden collapse when it causes tension physiology, compressing the heart and great vessels and severely compromising cardiac output and oxygenation.

Other Causes

Several additional conditions can cause sudden collapse, though they may not fit neatly into the categories above.

Anaphylaxis, a severe allergic reaction, can cause sudden collapse through massive vasodilation and fluid leakage from blood vessels, leading to a dramatic drop in blood pressure. Common triggers include foods, medications, insect stings, and latex. Anaphylaxis typically involves additional symptoms such as hives, facial swelling, and difficulty breathing.

Heat-related illnesses, including heat exhaustion and heat stroke, can cause collapse when thermoregulatory mechanisms fail. Heat stroke, in particular, represents a medical emergency characterized by high body temperature, altered mental status, and potential multi-organ dysfunction.

Psychogenic pseudosyncope refers to episodes of collapse that resemble syncope but result from psychological factors rather than physiological disturbances. These episodes may be related to conversion disorder, somatic symptom disorder, or factitious disorder. While not caused by underlying physiological abnormalities, these episodes are real to the person experiencing them and require appropriate evaluation and management.

Warning Signs and Symptoms

While sudden collapse often occurs without warning, many individuals experience symptoms before the event. Recognizing these warning signs can provide an opportunity to seek medical attention and potentially prevent a full collapse. The specific symptoms experienced depend on the underlying cause, but several common patterns have been identified.

Pre-syncope Symptoms

Pre-syncope refers to the symptoms experienced before loss of consciousness. Many individuals report a prodrome or warning period lasting seconds to minutes before collapse. Common pre-syncope symptoms include dizziness or lightheadedness, often described as a feeling of floating or unsteadiness. Visual disturbances frequently occur, including blurred vision, tunnel vision (loss of peripheral vision), or seeing spots or flashing lights.

Auditory symptoms may include ringing in the ears (tinnitus) or a sense that sounds are becoming distant or muffled. Many people experience a sensation of warmth or flushing, particularly in the face and upper body. Nausea and sometimes vomiting can occur, especially in vasovagal episodes. Sweating, often profuse and cold, commonly accompanies these symptoms.

Palpitations or an awareness of heartbeats may precede collapse in cardiac-related events. Some individuals describe chest discomfort or pressure, particularly when the collapse relates to myocardial ischemia or infarction. Shortness of breath can occur in cardiac, respiratory, or metabolic causes of collapse.

Neurological symptoms may include confusion, difficulty speaking, weakness, or numbness, particularly when the collapse relates to cerebrovascular events. Headache, especially if sudden and severe, may precede collapse in subarachnoid hemorrhage or migraines.

Symptoms During Collapse

The symptoms observed during a collapse provide important clues about the underlying cause. Observers should note the person’s appearance, movements, breathing pattern, and duration of the episode.

In vasovagal syncope, individuals typically appear pale and sweaty, with a slow heart rate and low blood pressure. They may experience brief muscle twitching but usually don’t have prolonged convulsions. The episode typically lasts less than a minute, with rapid recovery once the person is lying flat.

Cardiac-related collapses often involve more serious symptoms. Individuals may appear cyanotic (blue) due to inadequate oxygenation, and their breathing may be abnormal or absent. Convulsions may occur if cerebral perfusion is severely compromised. The heart rate may be extremely fast, extremely slow, or irregular. Recovery without medical intervention is less likely in cardiac causes compared to vasovagal episodes.

Seizure-related collapses typically involve convulsive movements, though absence seizures and some partial seizures may cause collapse without visible convulsions. During a seizure, individuals may have abnormal eye movements, drooling, or loss of bladder or bowel control. The post-ictal period after a seizure involves confusion and gradual recovery over minutes to hours, unlike the rapid recovery typical of vasovagal syncope.

Respiratory causes of collapse often involve obvious breathing difficulties, such as wheezing in asthma, stridor in upper airway obstruction, or rapid shallow breathing in pulmonary embolism. Individuals may appear anxious and cyanotic, using accessory muscles to breathe.

Post-collapse Symptoms

The symptoms experienced after regaining consciousness can help differentiate among causes of collapse. In vasovagal syncope, individuals typically recover quickly once lying flat, with resolution of symptoms within seconds to minutes. They may feel weak or tired afterward but usually return to normal relatively quickly.

After a seizure, individuals experience a post-ictal period characterized by confusion, drowsiness, headache, and sometimes muscle soreness. This period can last from minutes to hours, depending on the type and duration of the seizure.

Cardiac-related collapses often require medical intervention before recovery occurs. Without treatment, individuals may not regain consciousness or may experience recurrent collapse. Even after successful treatment, they may report chest pain, palpitations, or shortness of breath.

Individuals who have collapsed due to hypoglycemia typically recover rapidly once their blood glucose is normalized, though they may experience headache, fatigue, and confusion for some time after the event.

Red Flag Symptoms

Certain symptoms associated with collapse should be considered red flags, indicating a potentially serious underlying cause requiring urgent medical evaluation. These include chest pain or pressure, especially if it radiates to the arm, neck, or jaw, as this may indicate myocardial ischemia or infarction.

Sudden severe headache, often described as “the worst headache of my life,” may suggest subarachnoid hemorrhage. Significant shortness of breath, particularly if it occurs at rest, may indicate pulmonary embolism, heart failure, or other serious cardiopulmonary conditions.

Confusion, weakness or numbness on one side of the body, difficulty speaking, or visual disturbances may indicate stroke or TIA. Palpitations accompanied by dizziness or collapse may suggest serious arrhythmia.

Collapse during exertion, especially in young athletes, should raise suspicion for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or other structural heart abnormalities. Collapse without warning symptoms may also indicate a more serious underlying cause.

Absence of a clear trigger for collapse, such as standing up quickly, emotional distress, or pain, may suggest a more serious etiology. Recurrent episodes of collapse, particularly if they’re becoming more frequent or severe, warrant thorough medical evaluation.

Immediate Response to Sudden Collapse

When someone collapses suddenly, the immediate response can significantly impact the outcome. Knowing how to assess the situation and provide appropriate first aid can save lives and prevent further harm. The following sections outline the steps to take when encountering someone who has collapsed suddenly.

Initial Assessment

The first step in responding to a collapsed person is to ensure the scene is safe for both the rescuer and the victim. Check for potential hazards such as traffic, fire, electrical wires, or other dangers. If the scene is unsafe, do not approach; call for professional help immediately.

Once safety is confirmed, approach the collapsed person and check for responsiveness. Tap their shoulder firmly and shout loudly, “Are you okay?” If there is no response, the person is unconscious and requires immediate attention.

Next, assess breathing. Look for chest movement, listen for breath sounds, and feel for air movement from the mouth or nose for no more than 10 seconds. If the person is breathing normally, place them in the recovery position and monitor their condition while waiting for emergency services.

If the person is not breathing or only gasping (agonal breathing), which may sound like snorting, gurgling, or moaning, begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) immediately if you are trained. If not trained, follow the instructions provided by the emergency dispatcher when you call for help.

Calling for Help