Maintaining a Healthy Spine: The Key Factors You Need to Know

Our spine is more than just a column of bones—it is the central highway that carries nerves, supports movement, and protects the spinal cord. When we understand the variables that influence spinal health, we can take proactive steps to keep this vital structure functioning optimally throughout life. In this article we explore the major factors that affect spine health, back them up with scientific evidence, and provide practical recommendations you can start applying today.

1. Anatomy at a Glance

Before diving into the influencing factors, it helps to review the basic components of the spine:

| Structure | Description | Primary Function |

| Vertebrae | 33 individual bones (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacrum, coccyx) | Provide structural support & attachment points |

| Intervertebral Discs | Fibro‑cartilaginous cushions between vertebrae | Absorb shock and allow flexibility |

| Facet Joints | Paired joints at the back of each vertebra | Guide and limit motion, add stability |

| Ligaments & Muscles | Tensile soft‑tissue structures | Stabilize, move, and protect the spine |

| Spinal Cord & Nerves | Central nervous system pathway | Transmit motor and sensory signals |

Understanding how each piece works together clarifies why lifestyle, biomechanics, and medical conditions can have such a profound impact on spinal health.

“The spine is the most important structure in the human body—if it fails, the entire system collapses.”

— Dr. John H. McGill, orthopedic surgeon and spine researcher

2. Core Factors Influencing Spine Health

We have identified six broad categories that consistently appear in peer‑reviewed literature and clinical guidelines as the most influential determinants of a healthy spine.

| Factor | How It Affects the Spine | Evidence‑Based Strategies |

| Posture & Ergonomics | Prolonged slouching or forward head posture overloads cervical and lumbar discs, leading to degeneration and pain. | • Adjust workstation to maintain a neutral spine. • Use lumbar support cushions. • Take micro‑breaks every 30‑45 min. |

| Physical Activity & Strength | Regular movement promotes disc nutrition (through diffusion) and strengthens paraspinal muscles that support the vertebrae. | • Perform core‑stabilizing exercises (planks, bird‑dogs). • Include low‑impact cardio (walking, swimming). |

| Flexibility & Mobility | Limited range of motion forces compensatory movements that stress joints and ligaments. | • Daily stretch routine targeting hamstrings, hip flexors, thoracic spine. • Incorporate yoga or Pilates sessions. |

| Body Weight & Nutrition | Excess weight increases axial load; nutrient deficiencies impair disc matrix synthesis. | • Maintain BMI < 25 kg/m². • Eat a diet rich in omega‑3s, collagen‑supporting nutrients (vitamin C, zinc). |

| Sleep Quality & Mattress Choice | Inadequate spinal support during sleep disrupts recovery and can exacerbate chronic pain. | • Choose a medium‑firm mattress that keeps the spine in neutral alignment. • Use a pillow that supports the cervical curve. |

| Medical & Lifestyle Factors | Smoking reduces blood flow to discs, while stress elevates muscle tension, both accelerating degeneration. | • Quit smoking; consider nicotine‑replacement therapy. • Practice stress‑reduction techniques (mindfulness, breathing exercises). |

Each factor interacts with the others—poor posture can lead to muscle weakness, which may cause weight gain, and so on. A holistic approach that targets all six categories yields the most durable results.

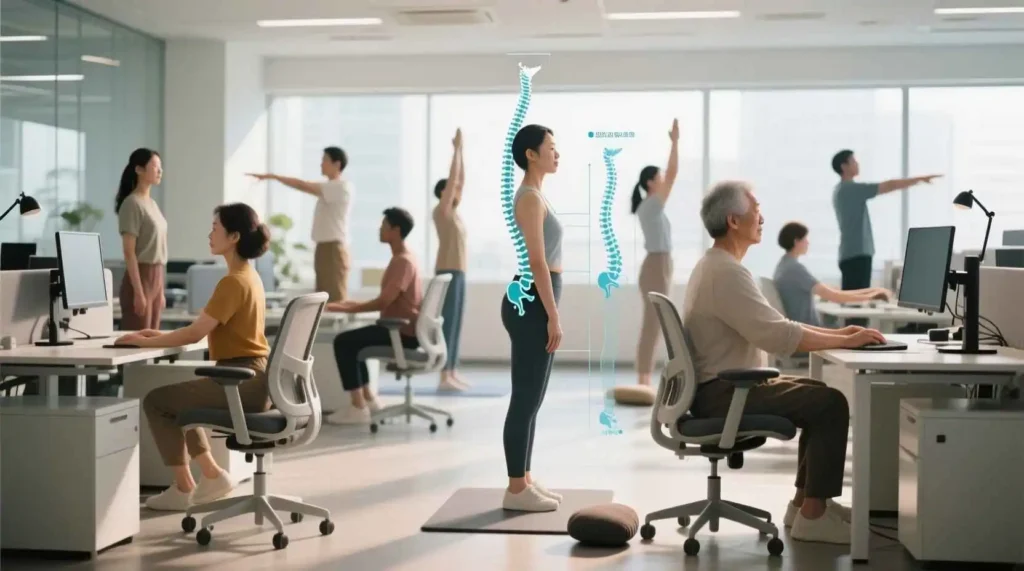

3. The Role of Posture: Why “Sitting is the New Smoking” Is Not Just a Catchphrase

The alarming declaration that “sitting is the new smoking” is more than just a catchy phrase; it’s a stark warning about the insidious, long-term health consequences of our increasingly sedentary modern lifestyles. For vast swathes of the population, particularly office workers, students, and those engaged in digital entertainment, prolonged sitting has become an unavoidable reality. The human body, however, is designed for movement, not for static, hunched postures. When we habitually sit for extended periods with a rounded back (kyphotic posture) and a forward head (cervical protraction), we impose detrimental stresses on our musculoskeletal system that can lead to chronic pain, reduced mobility, and even structural damage over time.

Let’s delve deeper into the specific impacts of poor sitting posture:

- Intervertebral Discs Experience Increased Pressure and Strain: The intervertebral discs, which act as natural shock absorbers and spacers between our vertebrae, are highly vulnerable. In a rounded back posture, the spine loses its natural S-curve, and the pressure on the discs becomes unevenly distributed. Specifically, the posterior corners of the discs bear the brunt of this increased compressive load. This persistent, unnatural pressure significantly hastens annular strain, leading to micro-tears and weakening of the disc’s tough outer fibrous ring (the annulus fibrosus). Over time, this can compromise the disc’s integrity, increasing the risk of disc bulging, herniation, and degenerative disc disease, often manifesting as sciatica or localized back pain.

- Hip Flexors Become Chronically Shortened, Disrupting Pelvic and Lumbar Alignment: The hip flexor muscles (primarily the iliopsoas and rectus femoris) are constantly in a shortened position when seated. Over prolonged periods, these muscles adapt by becoming tight and restricted. This chronic shortening subsequently pulls the pelvis into an anterior tilt, meaning the top of the pelvis rotates forward. This forward pelvic rotation, in turn, causes a flattening of the lumbar curve (loss of lumbar lordosis) or even a reversal of it. The lumbar lordosis is a crucial natural curve that aids in shock absorption and proper spinal biomechanics. Its loss places increased stress on the lower lumbar discs and facet joints, contributing directly to chronic lower back pain and stiffness.

- Neck Muscles Become Overactive, Leading to Headaches and Cervical Disc Stress: A forward head posture, often accompanying a rounded back, forces the head to jut forward, placing immense strain on the neck and upper back muscles. Muscles like the upper trapezius and levator scapulae become chronically overstretched and overactive as they struggle to counterbalance the weight of the head, which effectively increases its perceived weight on the spine. This constant muscular tension is a primary contributor to tension-type headaches, which often radiate from the base of the skull into the temples or forehead. Furthermore, the sustained compression on the cervical discs (in the neck) due to this forward posture significantly increases their susceptibility to stress, degeneration, and potential herniation, leading to neck pain, stiffness, and referred pain or numbness into the arms.

Simple Ergonomic Checklist: Your First Line of Defense

Fortunately, many of these postural pitfalls can be mitigated through simple yet impactful ergonomic adjustments to your workspace. Implementing these changes promotes a more neutral spinal alignment, reducing cumulative stress on your body.

- Screen Height – Top of the Monitor at Eye Level: Positioning the top of your monitor at eye level ensures that your head remains in a neutral position, directly above your shoulders. This prevents you from craning your neck forward or extending it backward to view the screen, thereby reducing strain on the cervical spine and the muscles of the neck and upper back.

- Keyboard Placement – Elbows at 90°, Forearms Parallel to the Floor: Your keyboard should be positioned so that your elbows form a 90-degree angle, with your forearms parallel to the floor and your wrists in a neutral, straight position. This minimizes strain on your wrists, forearms, and shoulders, preventing conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome and repetitive strain injuries.

- Chair Adjustment – Hips Slightly Higher Than Knees; Lumbar Support Fits the Natural Curve: Adjust your chair so that your hips are positioned slightly higher than your knees. This open hip angle encourages the natural lumbar curve and prevents the pelvis from tucking under (posterior tilt), which contributes to a rounded lower back. Crucially, ensure that your chair’s lumbar support firmly fits into the natural inward curve of your lower back. This support helps maintain the lumbar lordosis, evenly distributing pressure across the discs and reducing strain on the spinal ligaments and muscles.

- Foot Support – Feet Flat on the Floor or on a Footrest: Your feet should be flat on the floor, providing a stable base and promoting proper blood circulation in your legs. If your feet don’t comfortably reach the floor, use a footrest to ensure your knees are still at the recommended angle and to prevent pressure points on your thighs from the chair’s edge.

Implementing these seemingly minor adjustments can yield significant benefits. According to a compelling 2022 biomechanical study published in Spine, a highly respected journal in spinal research, adherence to these ergonomic principles can reduce overall spinal load by up to 30%. This quantifiable reduction in stress translates directly into decreased potential for pain, injury, and degenerative changes, empowering individuals to work and study more comfortably and sustainably. Beyond static ergonomics, integrating regular movement breaks, stretching, and strengthening exercises is also essential for a holistic approach to spinal health in our modern sedentary world.

4. Exercise Prescription for a Strong Spine

While any movement is better than none, certain exercises have shown superior benefits for spinal stability.

| Exercise | Targeted Structures | Sets & Reps (Beginner) | Progression Tips |

| Dead Bug | Deep core (transverse abdominis) | 3 × 10 each side | Add light ankle weights |

| Bird‑Dog | Lumbo‑pelvic stabilizers | 3 × 12 each side | Hold each extension for 5 s |

| Wall Angels | Thoracic mobility & scapular retractors | 2 × 15 | Perform with a resistance band |

| Glute Bridge | Gluteus maximus, posterior chain | 3 × 12 | Elevate feet onto a step for increased range |

| Side Plank | Lateral core, obliques | 2 × 30 s per side | Increase time by 10 s each week |

Consistency matters more than intensity. Aim for three sessions per week, each lasting 20‑30 minutes. Pair these with aerobic activities (e.g., brisk walking, cycling) for cardiovascular health, which indirectly supports spinal health by improving circulation to the discs.

5. Nutrition: Feeding the Intervertebral Discs

Intervertebral discs are avascular; they receive nutrients through diffusion from surrounding vessels. A diet that supports extracellular matrix synthesis can slow degeneration.

| Nutrient | Key Food Sources | Specific Benefits |

| Collagen Peptides | Bone broth, gelatin, collagen supplements | Provides amino acids (glycine, proline) for disc matrix |

| Omega‑3 Fatty Acids | Fatty fish, flaxseed, chia seeds | Anti‑inflammatory, reduces discogenic pain |

| Vitamin C | Citrus fruits, bell peppers, broccoli | Crucial for collagen cross‑linking |

| Zinc | Pumpkin seeds, legumes, meat | Supports cellular repair of disc cells |

| Magnesium | Nuts, leafy greens, whole grains | Relaxes muscular tension surrounding the spine |

A balanced diet with 1.2–1.5 g of protein per kilogram of body weight, 25–30 g of fiber, and adequate hydration (≥2 L water per day) creates an optimal internal environment for disc health.

6. Weight Management: Reducing Mechanical Load

Every kilogram of body weight adds roughly 10 N of force to the lumbar spine when standing. Even modest weight loss can produce measurable relief. A controlled review in The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery found that a 5 % reduction in body weight decreased low‑back pain intensity by 15 % on average.

Practical weight‑control tactics:

- Meal Timing: Adopt a 12‑hour eating window (e.g., 8 am–8 pm) to regulate insulin.

- Portion Control: Use the “hand” method—protein the size of your palm, carbs the size of a cupped hand, vegetables filling two hands.

- High‑Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): 15‑minute sessions 2‑3 times a week boost metabolism without overloading the spine.

7. Sleep Hygiene: The Nightly Reset

During deep sleep, the spine undergoes re‑hydration as the intervertebral discs absorb fluid. An unsupportive mattress can keep the spine in a compromised posture, impeding this restorative process.

Choosing the right sleep surface:

| Mattress Type | Typical Firmness | Ideal For |

| Memory Foam | Medium‑firm | Individuals with low back pain; conforms to body shape |

| Latex | Medium | Those who prefer a cooler surface with bounce |

| Hybrid (coils + foam) | Medium‑firm to firm | Heavier sleepers needing strong support |

| Innerspring | Firm | People who like a traditional “bouncy” feel and minimal sink |

A pillow that supports the natural cervical curve is equally vital. For side sleepers, a pillow aligning the head with the spine; for back sleepers, a thinner pillow with a small roll under the neck.

8. Lifestyle Risks: Smoking & Stress

Smoking reduces oxygen delivery to the disc cells, accelerating dehydration and loss of disc height. A meta‑analysis of 18 cohort studies reported a 2‑fold increase in the risk of disc herniation among smokers.

Stress triggers the sympathetic nervous system, causing muscles around the spine (especially the trapezius and erector spinae) to contract continuously. Chronic tension limits spinal mobility and can induce pain syndromes.

Mitigation strategies:

- Quit Smoking: Seek counseling, nicotine replacement, or prescription medications (e.g., varenicline).

- Stress Management: Integrate daily 5‑minute breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, or short mindfulness sessions.

9. Putting It All Together: A 4‑Week Action Plan

| Week | Focus | Daily/Weekly Activities |

| 1 | Posture & Ergonomics | Set up workstation; perform 5‑minute desk stretches every hour. |

| 2 | Core Strength & Mobility | 3×/week core circuit (dead bug, bird‑dog, side plank); 10‑minute thoracic stretch after each session. |

| 3 | Nutrition & Hydration | Add a collagen supplement; consume ≥2 L water; include omega‑3 fish twice weekly. |

| 4 | Sleep & Stress | Switch to a medium‑firm mattress if needed; practice 10‑minute guided meditation before bed. |

Track progress using a simple journal: note pain levels (0‑10 scale), sleep quality, and any changes in activity tolerance. Adjust the plan based on what works best for your body.

10. When to Seek Professional Help