Best Practices for Edema Relief: Symptoms, Causes and Treatments

Introduction

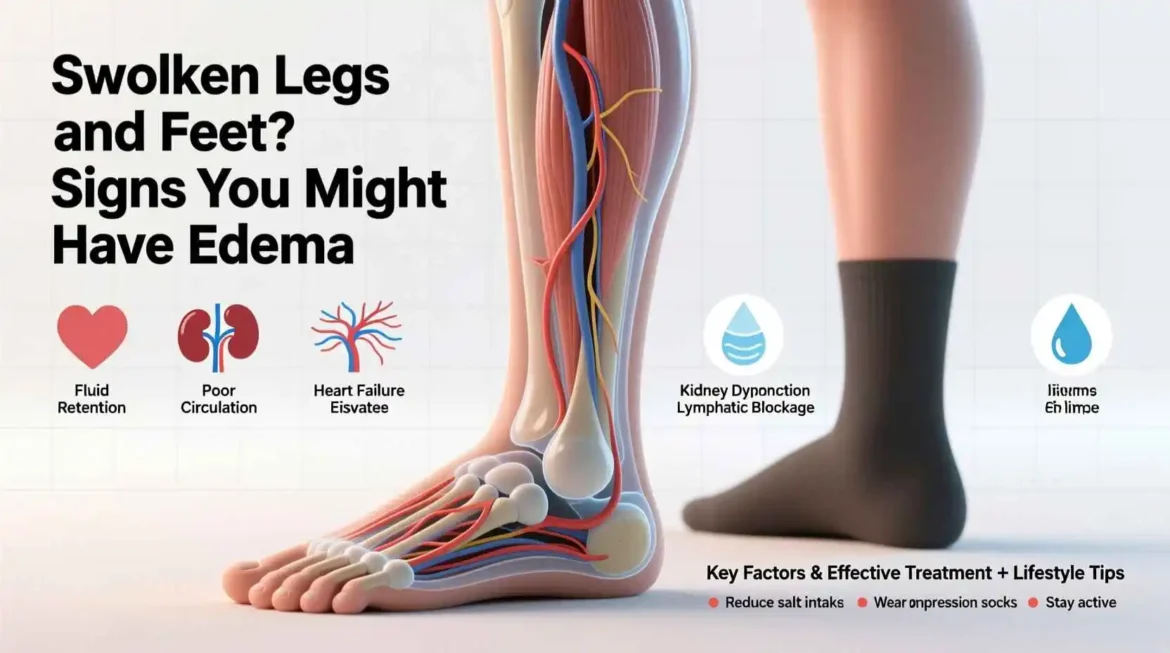

Edema, a condition characterized by swelling caused by excess fluid trapped in the body’s tissues, affects millions of people worldwide. This seemingly simple symptom can be a sign of something as benign as sitting too long or as serious as heart, kidney, or liver disease. The visible swelling that occurs with edema can be uncomfortable, unsightly, and sometimes painful, but more importantly, it often serves as a warning signal that something within the body’s complex fluid regulation system is out of balance.

Fluid balance in the human body is a marvel of biological engineering, involving intricate interactions between the circulatory system, the lymphatic system, the kidneys, and various hormones. When this delicate balance is disrupted, fluid can accumulate in the interstitial spaces—the areas between cells—leading to the swelling we recognize as edema. Understanding this condition requires exploring not just its visible manifestations, but the underlying physiological processes that govern fluid movement throughout the body.

Edema can affect anyone, regardless of age, gender, or health status. It might manifest as puffy eyes in the morning, swollen ankles after a long day of standing, or more generalized swelling throughout the body. For some, edema is a temporary inconvenience, while for others, it’s a chronic condition that significantly impacts quality of life. The approach to managing edema varies widely depending on its cause, severity, and location, making accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment essential.

In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the world of edema, exploring its various types, causes, symptoms, diagnostic approaches, and treatment strategies. We will examine how edema affects different parts of the body and discuss the latest research and medical approaches to managing this condition. By the end of this exploration, you will have a thorough understanding of edema and be equipped with practical knowledge to recognize, address, and prevent this common yet complex condition.

The Physiology of Fluid Balance in the Human Body

To truly understand edema, we must first appreciate the sophisticated mechanisms that maintain fluid balance in the human body. Under normal circumstances, the body maintains a delicate equilibrium between the fluids inside cells (intracellular fluid), in the blood (intravascular fluid), and in the spaces between cells (interstitial fluid). This balance is crucial for proper cellular function, blood volume regulation, and overall health.

The movement of fluid between these compartments is governed by several key principles. Starling’s forces describe the movement of fluid across capillary walls, where the balance between hydrostatic pressure (the force exerted by fluid against vessel walls) and oncotic pressure (the pulling force exerted by proteins, particularly albumin) determines whether fluid remains within blood vessels or leaks into surrounding tissues. When hydrostatic pressure exceeds oncotic pressure, fluid moves from the intravascular space into the interstitial space. Conversely, when oncotic pressure is higher, fluid is drawn back into the blood vessels.

The lymphatic system plays a crucial role in this balance by collecting excess interstitial fluid and returning it to the bloodstream. This network of vessels and nodes acts as a drainage system, preventing the accumulation of fluid in tissues. When the lymphatic system is compromised, as in lymphedema, fluid cannot be adequately removed, leading to swelling.

The kidneys also contribute significantly to fluid balance through their regulation of sodium and water excretion. Hormones such as aldosterone, antidiuretic hormone (ADH), and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) work in concert to maintain appropriate fluid volume and electrolyte balance. When any of these regulatory mechanisms are disrupted, edema can result.

Capillary permeability is another critical factor in fluid balance. Under normal conditions, capillary walls are selectively permeable, allowing certain substances to pass while restricting others. Inflammation, infection, or other pathological processes can increase capillary permeability, allowing proteins and fluid to leak into the interstitial space more readily, contributing to edema formation.

Understanding these physiological processes provides the foundation for recognizing how various conditions and factors can disrupt fluid balance and lead to edema. Whether due to increased capillary pressure, decreased oncotic pressure, impaired lymphatic drainage, or altered capillary permeability, the underlying mechanisms of edema all involve a disruption in the normal movement and regulation of body fluids.

Types of Edema

Edema can be classified in several ways, based on its location, duration, underlying cause, and characteristics. Understanding these different types is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment. The classification of edema helps healthcare providers determine the underlying cause and develop targeted treatment strategies.

Peripheral edema is perhaps the most commonly recognized form, affecting the extremities—particularly the legs, ankles, and feet. This type of edema is often visible as swelling that leaves an indentation when pressed, known as pitting edema. Peripheral edema can be localized or generalized, depending on the underlying cause. It’s frequently associated with conditions that affect circulation, such as venous insufficiency, heart failure, or prolonged periods of sitting or standing.

Pulmonary edema is a more serious condition characterized by fluid accumulation in the lungs. This type of edema can be life-threatening, as it interferes with gas exchange and can lead to respiratory failure. Pulmonary edema is often associated with heart problems, particularly left-sided heart failure, where increased pressure in the pulmonary vessels causes fluid to leak into the lung tissue. It can also result from acute lung injury, infections, or exposure to certain toxins.

Cerebral edema involves swelling in the brain and is particularly dangerous due to the confined space within the skull. Unlike other parts of the body, the brain has limited room to expand, making cerebral edema a medical emergency. This type of edema can result from traumatic brain injury, infections, tumors, stroke, or metabolic disturbances. The increased intracranial pressure associated with cerebral edema can lead to brain damage or death if not promptly treated.

Macular edema affects the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed vision. Fluid accumulation in this area can distort vision and, if left untreated, lead to permanent vision loss. Macular edema is often associated with diabetic retinopathy but can also result from retinal vein occlusion, inflammation, or eye surgery.

Lymphedema is a specific type of edema caused by impaired lymphatic drainage. Unlike other forms of edema that may resolve with treatment of the underlying cause, lymphedema is typically chronic and progressive. It often develops after lymph node removal or damage, commonly as a result of cancer treatment. Lymphedema can be primary, due to congenital abnormalities in the lymphatic system, or secondary, resulting from damage to the lymphatic system.

Periorbital edema refers to swelling around the eyes and is often most noticeable upon waking. This type of edema can result from various causes, including allergies, kidney disease, thyroid disorders, or simply sleeping position. Periorbital edema is usually painless but can be cosmetically concerning and may indicate underlying health issues.

Angioedema is a deeper form of edema that affects the lower layers of the skin and often involves the face, lips, tongue, and throat. Unlike other types of edema, angioedema is frequently caused by an allergic reaction and can be life-threatening if it affects the airway. This condition may be hereditary or acquired and is characterized by sudden, severe swelling that can come and go rapidly.

Idiopathic edema is a diagnosis of exclusion, used when no clear cause for the swelling can be identified despite thorough investigation. This type of edema primarily affects women and is often associated with fluid retention that varies with the menstrual cycle. Idiopathic edema can be frustrating for both patients and healthcare providers due to its unclear etiology and variable response to treatment.

Understanding these different types of edema is crucial for determining the appropriate diagnostic approach and treatment strategy. Each type has unique characteristics, causes, and implications, requiring tailored management plans to address the specific underlying mechanisms and symptoms.

Causes of Edema

The causes of edema are diverse and multifactorial, reflecting the complex nature of fluid regulation in the human body. Edema can result from localized issues affecting a specific area or systemic conditions that impact the entire body. Understanding these causes is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Cardiovascular causes are among the most common systemic reasons for edema. Heart failure, particularly right-sided heart failure, leads to increased pressure in the venous system, causing fluid to leak into surrounding tissues. In left-sided heart failure, the backup of blood in the pulmonary circulation can result in pulmonary edema. Other cardiovascular causes include venous insufficiency, where damaged valves in the veins allow blood to pool in the extremities, and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), where a blood clot obstructs venous return, leading to localized swelling.

Renal or kidney-related causes of edema involve the kidneys’ impaired ability to regulate fluid and electrolyte balance. In nephrotic syndrome, excessive loss of protein in the urine reduces plasma oncotic pressure, allowing fluid to move into tissues. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease can also lead to fluid retention and edema due to impaired sodium and water excretion. Additionally, renal artery stenosis can activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, promoting sodium and water retention.

Hepatic or liver-related causes of edema are primarily associated with advanced liver disease, particularly cirrhosis. In cirrhosis, liver damage leads to decreased production of albumin, reducing plasma oncotic pressure. Additionally, portal hypertension increases pressure in the abdominal veins, contributing to ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity) and peripheral edema. The liver’s role in hormone metabolism also affects fluid balance, as impaired breakdown of aldosterone can lead to increased sodium retention.

Endocrine disorders can also cause edema through various mechanisms. Hypothyroidism can lead to myxedema, a specific type of non-pitting edema characterized by the accumulation of glycosaminoglycans in the skin. Cushing’s syndrome, characterized by excess cortisol production, can cause sodium and water retention. Severe vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency, known as beriberi, can lead to wet beriberi, characterized by high-output heart failure and peripheral edema.

Inflammatory and infectious causes of edema involve increased capillary permeability, allowing fluid and proteins to leak into tissues. Conditions such as cellulitis, a bacterial skin infection, can cause localized edema, erythema, and warmth. Inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis can lead to joint swelling and edema. Burns and trauma can also cause localized edema due to tissue damage and inflammation.

Medication-related edema is a common cause that healthcare providers must consider. Many medications can cause fluid retention, including calcium channel blockers used for hypertension, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), certain hormones like estrogen and testosterone, and some antidepressants. Chemotherapy drugs can also cause peripheral edema as a side effect. In many cases, medication-induced edema resolves once the offending drug is discontinued or the dosage is adjusted.

Nutritional factors can contribute to edema development. Severe protein deficiency, as seen in kwashiorkor, reduces plasma oncotic pressure, leading to generalized edema. Thiamine deficiency, as mentioned earlier, can cause wet beriberi with associated edema. Excessive sodium intake can overwhelm the kidneys’ ability to excrete sodium, leading to fluid retention and edema, particularly in individuals with compromised cardiac or renal function.

Lifestyle and environmental factors can also cause or exacerbate edema. Prolonged sitting or standing can lead to dependent edema, particularly in the lower extremities. High altitudes can cause peripheral edema due to changes in atmospheric pressure and fluid regulation. Heat exposure can cause vasodilation and increased capillary permeability, contributing to edema formation. Pregnancy is another common cause of edema due to hormonal changes, increased blood volume, and pressure from the growing uterus on the venous system.

Idiopathic cyclic edema is a poorly understood condition primarily affecting women, characterized by episodes of edema that often follow a menstrual cycle pattern. The exact cause remains unclear, but it may involve abnormal capillary permeability, hormonal fluctuations, or sodium retention issues.

Understanding these diverse causes of edema is crucial for healthcare providers to develop appropriate diagnostic and treatment strategies. In many cases, multiple factors contribute to edema development, requiring a comprehensive approach to address all underlying issues effectively.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Edema