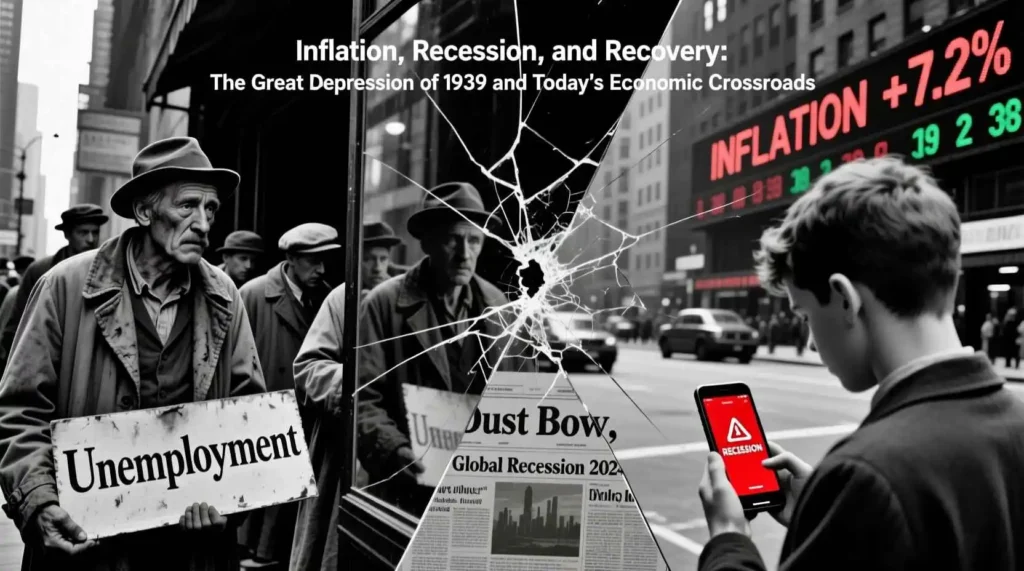

The Great Depression of 1939 and Its Impact on Current Global Markets

Introduction

The year 1939 represents a pivotal moment in world history, standing at the intersection of the Great Depression’s lingering effects and the impending storm of World War II. While the most severe years of the Depression (1929-1933) had passed, the global economy in 1939 remained fragile, incompletely recovered, and fundamentally transformed by the economic catastrophe that had reshaped capitalism, governments, and societies worldwide. Understanding the economic conditions of this specific year provides valuable insights into the resilience of economies facing crisis and offers meaningful parallels to our contemporary economic challenges.

This comprehensive examination will explore the state of the global economy in 1939, analyzing the lingering effects of the Great Depression, the recovery efforts that had been implemented, and the economic conditions that characterized this transitional year. Furthermore, we will draw meaningful connections between the economic realities of 1939 and today’s global economic landscape, identifying patterns, lessons, and warning signs that remain relevant to policymakers, economists, and citizens in the 21st century.

The Economic Landscape of 1939

Global Economic Conditions

By 1939, the world economy had made significant strides from the depths of the Depression but had not fully recovered to pre-1929 levels. The international economic system remained fractured, characterized by protectionism, currency instability, and uneven development across different regions. The global economic order that had existed before 1929—with its commitment to free trade, the gold standard, and limited government intervention—had been irrevocably altered.

In 1939, international trade remained substantially below pre-Depression levels. The protectionist policies that had been implemented during the crisis years, most notably the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in the United States, had created a fragmented global trading system. Bilateral trade agreements and preferential trading blocs had replaced the more universal approach to international commerce that had characterized the pre-Depression era.

The gold standard, which had been abandoned by most countries during the worst years of the Depression, had not been restored in its previous form. Instead, managed currencies and exchange controls had become common features of the international monetary system. This shift reflected a broader acceptance of government management of monetary policy as a necessary tool for economic stabilization.

The United States Economy in 1939

The United States economy in 1939 presents a complex picture of partial recovery and persistent challenges. The unemployment rate, while significantly improved from the 25% peak of 1933, remained stubbornly high at approximately 17% in 1939. Gross National Product (GNP) had grown substantially since 1933 but was still about 10% below its 1929 peak.

The New Deal programs implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt had transformed the relationship between the federal government and the economy. By 1939, programs such as the Social Security Act, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had become established features of the American economic landscape. These initiatives represented a fundamental shift toward greater government responsibility for economic security and regulation.

However, the American economy in 1939 remained vulnerable to setbacks. The “Roosevelt Recession” of 1937-1938 had demonstrated the fragility of the recovery, with GNP declining by 10% and unemployment rising by several percentage points. This downturn was largely attributed to fiscal and monetary tightening as policymakers, concerned about budget deficits and inflation, had reduced government spending and tightened monetary policy.

The European Economic Situation

Europe in 1939 presented a diverse economic picture, with significant variations between countries. The United Kingdom had experienced a relatively earlier and more robust recovery than many other European nations. By 1939, British unemployment had declined significantly from its peak, though it remained elevated by pre-Depression standards. The British economy had benefited from the abandonment of the gold standard in 1931, which had allowed for more flexible monetary policy, and from a gradual reorientation toward imperial preference and protectionism.

France, by contrast, had experienced a more difficult path. The country had remained committed to the gold standard until 1936, delaying necessary policy adjustments. The French economy in 1939 remained stagnant, with high unemployment and persistent industrial weakness. Political instability had further complicated economic policymaking, with frequent changes in government hindering consistent economic strategies.

Germany’s economy in 1939 presents a special case, as it had been fundamentally transformed by the Nazi regime’s rearmament policies and autarkic economic strategies. Official unemployment statistics had virtually disappeared by 1939, but this reflected massive military spending, forced labor programs, and the removal of women from official unemployment counts rather than genuine economic health. The German economy was increasingly directed toward war preparation, with severe controls on consumption, investment, and foreign exchange.

The Soviet Union, operating outside the capitalist world system, had pursued rapid industrialization through centralized planning. By 1939, the Soviet economy had grown substantially in industrial output, though at tremendous human cost and with significant inefficiencies. The Soviet model represented a fundamentally different approach to economic organization that some observers in capitalist countries viewed with interest as an alternative to the market system that had seemingly failed during the Depression.

The Asian and Colonial Economies

The economic situation in Asia in 1939 was closely tied to colonial relationships and the approaching conflict. Japan, which had invaded China in 1937, had developed an economy increasingly directed toward military expansion. The Japanese government implemented strict economic controls, focusing on heavy industry and military production while consumer goods remained scarce.

China, meanwhile, suffered from both the Japanese invasion and the lingering effects of the global Depression. The Chinese economy remained predominantly agricultural, with limited industrial development. The conflict with Japan had devastated economic activity in many regions and created massive refugee flows.

In European colonies across Asia and Africa, the Depression had led to declining demand for raw materials and agricultural products, causing economic hardship. Colonial governments had generally responded with austerity measures that fell disproportionately on native populations. By 1939, many colonial economies remained depressed, with limited investment and development.

Economic Policies and Approaches in 1939

Fiscal Policy Approaches

By 1939, the debate over fiscal policy had been fundamentally transformed by the Depression experience. The pre-Depression consensus favoring balanced budgets and limited government spending had been challenged by the reality of prolonged economic stagnation. The ideas of John Maynard Keynes, which argued for deficit spending during economic downturns to stimulate demand, had gained significant traction among economists and policymakers.

In the United States, the New Deal represented an embrace of deficit financing for public works and relief programs, though Roosevelt remained ambivalent about deficit spending and had attempted to balance the budget in 1937 with disastrous results. By 1939, however, the administration had returned to more expansionary fiscal policies, recognizing that premature fiscal tightening could derail the recovery.

In Europe, fiscal policy approaches varied significantly. The United Kingdom had pursued relatively moderate deficit spending, while France had maintained a more conservative fiscal stance until very recently. Germany, as mentioned earlier, had engaged in massive deficit spending, but primarily for military purposes rather than economic stimulus.

Monetary Policy Developments

Monetary policy in 1939 reflected the lessons learned during the Depression. The Federal Reserve, having been widely criticized for its contractionary policies during the early 1930s, had adopted a more accommodative stance. Interest rates remained low, and the Fed stood ready to provide liquidity to the banking system.

The abandonment of the gold standard by most countries had given central banks greater freedom to pursue expansionary monetary policies. This flexibility represented a significant departure from the pre-Depression era, when the gold standard had severely constrained monetary policy options.

However, monetary policy faced limitations in 1939. The liquidity trap phenomenon—where interest rates are so low that further reductions have little stimulative effect—had become apparent in several countries. This recognition would later inform Keynes’s argument that fiscal policy might be necessary when monetary policy alone proved insufficient.

International Economic Cooperation and Conflict

The international economic system in 1939 remained characterized by conflict rather than cooperation. The League of Nations had attempted to promote economic coordination through conferences such as the London Economic Conference of 1933, but these efforts had largely failed due to conflicting national interests and the rise of economic nationalism.

Bilateral trade agreements had become the preferred approach to international economic relations. The United States, under Secretary of State Cordell Hull, had negotiated reciprocal trade agreements with numerous countries, reducing tariffs on a selective basis. However, these agreements could not fully compensate for the overall decline in international trade.

The approach of war had further complicated international economic relations. Countries increasingly viewed economic policy through the lens of national security, prioritizing self-sufficiency and military preparedness over international cooperation. This trend would accelerate dramatically after 1939, fundamentally reshaping the global economic system.

Social Impacts and Demographic Patterns

Unemployment and Labor Markets

The labor market in 1939 remained scarred by the Depression. While unemployment rates had declined from their peak, they remained elevated by historical standards. In the United States, approximately 17% of the workforce was unemployed, with rates significantly higher among certain demographic groups.

Long-term unemployment had become a persistent problem. Many workers who had lost their jobs during the Depression years had struggled to find new employment, leading to a deterioration of skills and employability. This phenomenon was particularly acute among older workers and those in industries that had contracted permanently.

The nature of work had also changed during the Depression years. Unionization had increased significantly in many countries, as workers sought greater protection against economic volatility. In the United States, the Wagner Act of 1935 had facilitated union organizing, leading to substantial growth in union membership. By 1939, labor unions had become powerful economic and political actors, advocating for better wages, working conditions, and social protections.

Poverty and Inequality

The Depression had dramatically increased poverty rates across the developed world. By 1939, while some improvement had occurred, poverty remained widespread. In the United States, despite the New Deal’s relief efforts, substantial segments of the population continued to live in deprivation, particularly in rural areas.

Inequality had declined somewhat from its pre-Depression peak, as the wealthy had suffered significant losses during the stock market crash and subsequent economic contraction. However, the distribution of income and wealth remained highly unequal by historical standards. The Depression experience had, however, made inequality a more prominent political issue, with calls for redistribution gaining traction across the political spectrum.

Demographic Changes

The Depression had significant demographic effects that were still apparent in 1939. Birth rates had declined sharply during the worst years of the crisis, as families postponed childbearing due to economic uncertainty. Marriage rates had similarly fallen. By 1939, as economic conditions improved, these rates had begun to recover but remained below pre-Depression levels.

Migration patterns had also been affected. International migration had declined substantially during the 1930s, as countries imposed stricter immigration controls amid economic hardship. Internal migration, however, had increased in many countries, as people moved in search of economic opportunity. In the United States, for example, the Dust Bowl had prompted significant migration from the rural Midwest to California and other western states.

Social and Cultural Responses

The social and cultural impact of the Depression extended beyond economic statistics. The experience of prolonged economic hardship had fundamentally shaped attitudes toward government, the market, and social responsibility. By 1939, there was a widespread expectation that governments had a responsibility to ensure economic security and provide a basic safety net for citizens.

This shift in attitudes was reflected in the cultural landscape of 1939. Literature, film, and art often addressed themes of economic hardship, social injustice, and human resilience. The works of John Steinbeck, such as “The Grapes of Wrath” (1939), captured the struggles of displaced farmers and became cultural touchstones for understanding the Depression experience.

Political radicalism had also grown during the Depression years, as extremist movements on both the left and right gained support by promising solutions to economic crisis. By 1939, the rise of fascism in Europe and the growing influence of communist parties in many countries reflected the political consequences of economic instability.

The Technological and Industrial Landscape

Technological Innovation During the Depression

Contrary to the common perception that the Depression was a period of technological stagnation, the 1930s saw significant innovation in various fields. The economic crisis had created incentives for businesses to develop labor-saving technologies and more efficient production methods. By 1939, several important technological developments had emerged that would shape the post-war economy.

In the United States, industrial research laboratories had expanded during the 1930s, as companies sought to develop new products and improve efficiency. Significant advances were made in fields such as aviation, telecommunications, and chemicals. The development of synthetic materials, particularly nylon by DuPont in 1935, represented a major innovation that would have widespread industrial applications.

The automobile industry, despite the decline in sales during the Depression years, had continued to innovate. By 1939, automobiles were more reliable, efficient, and comfortable than their pre-Depression counterparts. The development of automatic transmissions, improved braking systems, and more powerful engines had made driving more accessible to the average consumer.

Industrial Structure and Organization

The Depression had accelerated existing trends toward industrial concentration. By 1939, many industries were dominated by a few large firms that had survived the crisis by achieving economies of scale and scope. This concentration was particularly evident in industries such as steel, automobiles, and chemicals.

The relationship between government and industry had also been transformed. In the United States, the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), though ultimately ruled unconstitutional, had established the principle of industry-government cooperation. By 1939, many industries operated under codes of fair competition that had been developed during the NIRA period and later maintained through voluntary compliance or new legislation.

The labor movement had become a more powerful force in industrial relations. The rise of industrial unionism, particularly through the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), had fundamentally changed the balance of power between workers and employers. By 1939, collective bargaining had become established in many major industries, leading to higher wages and better working conditions for industrial workers.

Agricultural Transformation