Understanding Diastematomyelia: A Rare Spinal Condition

As we journey through the complexities of human anatomy and development, we occasionally encounter rare conditions that challenge our understanding of how the body is formed. One such condition is Diastematomyelia, a congenital malformation of the spinal cord that, while uncommon, has significant implications for those affected. It is a condition that begins before birth but whose effects can ripple throughout a person’s life. In this article, we will delve into the intricate details of Diastematomyelia, exploring its causes, the symptoms it presents, the methods used for diagnosis, and the modern treatments that offer hope and improved quality of life.

What Exactly is Diastematomyelia? Unraveling a Complex Spinal Condition

At its core, Diastematomyelia (DM) is a fascinating yet challenging congenital anomaly of the spine and spinal cord. It falls under the umbrella term of spinal dysraphism, a broad category encompassing various birth defects that arise from incomplete or improper closure of the neural tube during the very early stages of embryonic development, typically within the first few weeks of pregnancy. While the neural tube normally fuses to form the brain and spinal cord, in cases of dysraphism, this process is disrupted.

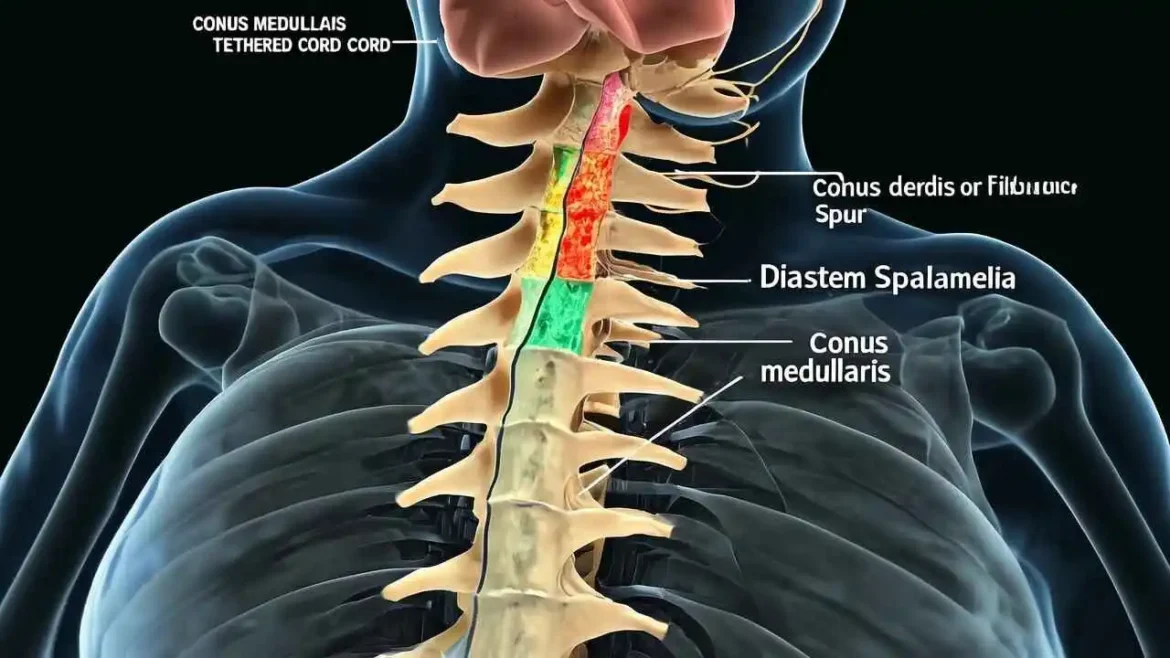

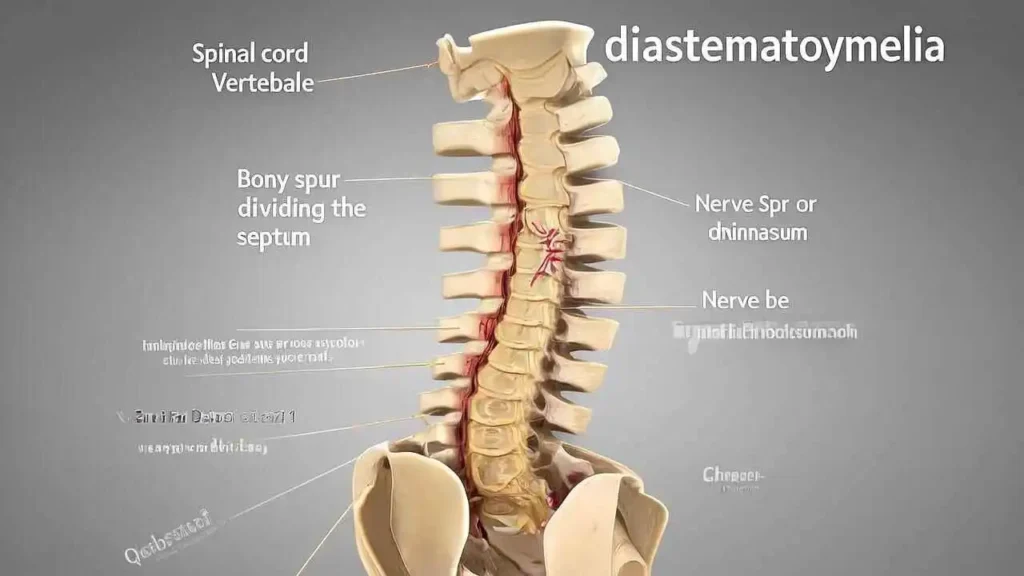

The defining characteristic of Diastematomyelia, specifically, is a longitudinal split or cleft within the spinal cord itself. Unlike other neural tube defects that might involve an open lesion or malformation, DM uniquely features a division running vertically along the cord, often resembling a forked path. This division effectively creates, in essence, two separate “hemicords” (half-cords), each containing a portion of the nerve fibers and gray matter, but potentially functioning independently or abnormally. This split most commonly occurs in the lower thoracic or lumbar regions of the spine, though it can manifest at any level.

This split in the spinal cord is far from being merely an empty space or a simple anatomical curiosity. It is profoundly significant because it is caused by the presence of a rigid septum, or a dividing wall, that grows abnormally through the center of the spinal canal. This septum can be composed of various tissues: it might be a hard piece of bone, firmer cartilage, or a dense, unyielding band of fibrous tissue. Regardless of its composition, this septum acts as a physical barrier, impaling and directly dividing the delicate spinal cord tissue.

Crucially, this septum acts as an immovable anchor for the spinal cord. This anchoring effect often leads to a secondary and more commonly known neurological condition: tethered cord syndrome (TCS). Normally, as a child grows from infancy through adolescence, the vertebral column (the bony spine) lengthens significantly. Concurrently, the spinal cord, which is somewhat elastic, is supposed to ascend freely within the spinal canal to accommodate this growth. However, when the spinal cord is tethered or held in place by the rigid septum of diastematomyelia, it cannot ascend as it normally would. Instead, this growth causes an unnatural stretching and tension on the spinal cord. This chronic stretching compromises the blood supply to the cord and interferes with the transmission of nerve signals, which is what ultimately causes a range of progressive neurological symptoms. These symptoms can include lower back pain, leg weakness or numbness, foot deformities, and bladder or bowel dysfunction, often worsening with age and growth spurts.

Classifying Diastematomyelia: Type I vs. Type II

To better understand and manage this condition, Diastematomyelia is traditionally categorized into two primary classifications, based on the arrangement of the dural sac and the nature of the dividing septum:

- Type I Diastematomyelia: In this more severe form, the defining characteristic is that each half of the split spinal cord (each hemicord) is encased within its own individual dural sac. The dura mater is the tough, protective outer membrane that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. In Type I, this membrane is also duplicated around the split segments. Critically, these two separate dural sacs are almost always completely and rigidly separated by a bony septum. This bony division is typically quite robust and inflexible, creating a very firm anchor for the cord. Type I is generally considered more symptomatic and is often associated with more pronounced neurological deficits due to the extreme rigidity and effective dual-anchoring of the cord.

- Type II Diastematomyelia: In contrast, with Type II Diastematomyelia, the split spinal cord is contained within a single, unified dural sac. Although the spinal cord itself is still divided, the surrounding protective membrane remains intact as one continuous structure. The dividing septum in Type II is typically more fibrous or cartilaginous and less rigid than the bony septum found in Type I. While it still acts as an anchor and can cause tethered cord syndrome, the fibrous nature may allow for slightly more “give” and potentially lead to less severe or later-onset symptoms compared to Type I, though significant neurological impairment can still occur.

Understanding these classifications is vital for accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and the planning of appropriate surgical interventions, which are often necessary to release the tethered cord and remove the offending septum.

The Root Causes: Unraveling a Congenital Puzzle

Diastematomyelia, a distinct and often complex spinal malformation, presents a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic challenge in developmental biology. We understand definitively that Diastematomyelia is congenital, a term signifying that it is present at the time of birth, rather than being acquired later in life. Its genesis can be traced back to the very earliest stages of human development, precisely during the first month of fetal development. This exceedingly critical period is a time of rapid and intricate cellular organization, where the most fundamental structures of the future body plan are laid down. Specifically, this is when the neural tube—the crucial precursor to the entire central nervous system, encompassing both the brain and the spinal cord—is forming, folding, and undergoing a vital process of closure.

The precise etiology, or the exact reason why this specific malformation occurs, remains a subject of ongoing scientific inquiry and is not yet fully understood. However, prevailing theories suggest that Diastematomyelia is a multifactorial process. This means it likely arises from a complex interplay of various elements rather than a singular, identifiable cause.

The leading theory points to an error or aberration during embryogenesis, the intricate process of embryonic development from conception to the formation of distinct organs and systems. This hypothesis posits that an aberrant or persistent connection forms prematurely between the anterior (front/ventral) and posterior (back/dorsal) parts of the developing embryo. Instead of allowing the neural tube to coalesce and close cleanly into a single, unified structure, this abnormal connection improperly cleaves or longitudinally splits the developing neural tube. This division results in the characteristic duplication or splitting of the spinal cord (or filum terminale), which is the hallmark of Diastematomyelia.

While the exact “trigger” for this specific embryological error remains elusive, potential contributing factors are thought to involve a combination of genetic predispositions and environmental influences. Genetic predispositions could refer to subtle, inherited tendencies or variations in genes that regulate neural tube development, even if a direct, single gene mutation hasn’t been definitively identified. Environmental influences might encompass a range of external factors encountered by the mother during early pregnancy, although these are less clearly defined for Diastematomyelia specifically.

It is noteworthy that, although a direct and strong causal link is not as firmly established as with other, more common neural tube defects like spina bifida, inadequate intake of folic acid during early pregnancy is still often considered a potential risk factor. Folic acid (Vitamin B9) plays a vital role in DNA synthesis and cell division, processes critical for the rapid growth and closure of the neural tube. Therefore, while not a definitive cause, ensuring sufficient folic acid intake, ideally beginning prior to conception and continuing through the first trimester, is a general recommendation for all pregnancies to mitigate the risk of neural tube defects. The “puzzle” of Diastematomyelia continues to drive research, aiming to fully elucidate the complex pathway of its origin.

Recognizing the Signs: Symptoms Across the Lifespan

The clinical presentation of Diastematomyelia is remarkably diverse, making early diagnosis challenging but crucial. Its manifestations vary significantly, primarily influenced by the patient’s age and the degree to which the spinal cord is tethered or stretched. This variability means that while some individuals, particularly those with a less severe form or minimal tethering, may never experience symptoms and remain asymptomatic throughout their lives, for others, signs of the condition emerge at different life stages. These symptoms are often precipitated or exacerbated by periods of rapid growth, such as during childhood and adolescence, or even by seemingly minor trauma that further stresses the already tethered spinal cord, leading to neurological or orthopedic dysfunction.

For newborns and young children, one of the most significant and often earliest indicators is the presence of distinctive cutaneous stigmata. These are visible, non-invasive markers found directly on the skin of the lower back, overlying the compromised area of the spinal column and cord. They are crucial clues for pediatricians and primary care providers, as they are present in over 50% of confirmed Diastematomyelia cases. Their presence suggests an underlying developmental anomaly of the spine and spinal cord, making them a red flag that warrants immediate further investigation.

Common Cutaneous Markers:

- A tuft of coarse, dark hair (hypertrichosis): This typically presents as a localized patch or tuft of unusually coarse, dark hair, often resembling a “faun’s tail,” found directly over the lower spine. It’s a key indicator of underlying spinal dysraphism.

- A deep dimple or pit (dermal sinus tract): This is a deep, sometimes wide, dimple or pit that may extend inward, potentially connecting to the spinal canal. These tracts can be a significant concern as they provide a pathway for infection to reach the central nervous system.

- A fatty lump (lipoma): A soft, palpable subcutaneous lipoma or swelling under the skin, feeling somewhat distinct from the surrounding tissue, typically located in the lumbosacral region. Its presence can indicate a deeper connection to the spinal cord.

- A red or purple birthmark (hemangioma/vascular malformation): This presents as a discolored patch of skin, typically red, purple, or bluish, caused by an abnormal collection of blood vessels. Its location over the spine can be indicative of an underlying spinal abnormality.

- A small tail-like appendage: Though rare, this highly specific finding presents as a small, soft, often rudimentary, tail-like projection extending from the lower back.

The identification of any of these cutaneous markers should always prompt a thorough neurological examination and diagnostic imaging, typically an MRI of the spine, to confirm or rule out an underlying spinal cord abnormality. Beyond these visible external signs, the actual symptoms of Diastematomyelia primarily manifest as progressive orthopedic and neurological dysfunction. Left untreated, the continuous stretching and damage to the spinal cord due to tethering often lead to a gradual worsening of symptoms, potentially causing irreversible deficits and impacting quality of life. The subsequent sections will detail these orthopedic and neurological manifestations across different age groups.

“The primary goal of surgery for symptomatic diastematomyelia is not to reverse existing neurological damage, which can be permanent, but to halt its progression. By untethering the cord, we give the patient the best possible chance to maintain their current function and prevent future decline.” – Guiding Principle from the Neurosurgical Community

The following table provides a general overview of how symptoms may present at different ages.

| Age Group | Common Symptoms & Signs |

| Infants & Toddlers | – Visible cutaneous stigmata on the lower back. – Asymmetry in leg size or muscle mass. – Foot deformities (e.g., clubfoot, high arches). – Unexplained weakness or differences in leg movement. |

| Children & Adolescents | – Progressive scoliosis (curvature of the spine) that is often rigid and difficult to treat. – Back pain, especially with activity. – Leg pain, numbness, or tingling. – Clumsiness, frequent tripping, or a worsening gait. – Onset of bladder or bowel control problems (e.g., new-onset bedwetting, incontinence). |

| Adults | – Chronic, debilitating low back and leg pain (sciatica). – Sensory loss in the legs or perineal area. – Progressive muscle weakness or atrophy in the legs. – Bladder and bowel dysfunction, which can become severe. |

The Path to Diagnosis: Unraveling Diastematomyelia

A diagnosis of Diastematomyelia, a rare congenital spinal condition, meticulously follows a structured pathway that seamlessly combines comprehensive physical assessment with cutting-edge medical imaging. This systematic approach is crucial for early and accurate identification, which can significantly impact long-term management and outcomes by preventing progressive neurological deficits.

1. Physical and Neurological Examination: The Initial Assessment

The diagnostic journey commences with a thorough and meticulous evaluation performed by a skilled clinician, often a pediatrician, neurologist, or neurosurgeon. This initial step is vital for uncovering both overt and subtle indicators of the condition:

- Inspection for Cutaneous Markers: The doctor will carefully inspect the patient’s back, particularly along the midline of the spine, for any cutaneous markers. These superficial skin manifestations can serve as crucial external clues to an underlying spinal defect. Common examples include a localized patch of increased hair growth (hairy tuft), a deep dimple or pit, a fatty lump (lipoma), a red or purple birthmark (hemangioma), or a small skin tag. While not all individuals with Diastematomyelia will present with these markers, their presence significantly raises suspicion.

- Detailed Neurological Examination: Beyond external signs, a comprehensive neurological exam is paramount. This assessment systematically evaluates various aspects of the nervous system to detect any signs of spinal cord or nerve root dysfunction. The clinician will meticulously assess:

- Muscle Strength: Looking for any signs of weakness, muscle imbalance, or atrophy (wasting), particularly in the lower extremities.

- Sensation: Testing the patient’s ability to perceive light touch, pain, temperature, and vibration in different dermatomes (areas of skin supplied by a single spinal nerve) to identify areas of numbness, altered sensation, or hypersensitivity.

- Reflexes: Checking deep tendon reflexes (e.g., knee jerk, ankle jerk) for asymmetry, absence, diminution, or exaggeration, which can indicate specific levels of spinal cord or nerve root involvement.

- Gait and Balance: Observing the patient’s walking pattern for any abnormalities such as foot drop, limp, scissoring gait, or instability, which often result from motor weakness or sensory deficits caused by the tethered cord.

- Assessment for Orthopedic Deformities: The examination may also identify associated orthopedic issues like scoliosis (sideways curvature of the spine), pes cavus (high-arched feet), or other foot deformities, which can arise due to chronic neurological impingement. The goal is to detect any subtle or progressive deficits that might suggest the spinal cord is being stretched or compressed by the splitting defect.

2. Initial Imaging: Providing the First Glimpse

Following the clinical examination, initial imaging studies are often employed to visualize the spinal column and its contents, guiding further diagnostic steps:

- Spinal Ultrasound (for Infants): For infants, especially those under 4-6 months of age, a spinal ultrasound is frequently the preferred initial imaging modality. This non-invasive, radiation-free technique is effective due to the incompletely ossified (bony) posterior elements of an infant’s spine, which allow the sound waves to penetrate and visualize the spinal cord, the conus medullaris (the tapered end of the spinal cord), and sometimes even the dividing septum itself. It’s an excellent screening tool for identifying a low-lying or tethered cord and potential associated abnormalities. As the child grows and bone ossifies, the utility of ultrasound diminishes.

- Plain X-rays (for Older Children and Adults): For older children and adults, plain X-rays of the spine serve as a valuable initial step. While X-rays primarily visualize bony structures and cannot directly show the spinal cord, they are highly useful for identifying associated bony abnormalities of the spine that are frequently seen in Diastematomyelia. These can include scoliosis, vertebral body anomalies (e.g., hemivertebrae, fused vertebrae), widened interpedicular distance (indicating a larger spinal canal), or the presence of a bony spur (if present) that may be splitting the spinal cord. X-rays provide a foundational anatomical overview and can help direct the focus for more advanced imaging.

3. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The Gold Standard

When Diastematomyelia is suspected, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is universally recognized as the gold standard for definitive diagnosis. This powerful imaging technique provides unparalleled detail of the soft tissues within the spinal canal:

- Comprehensive Visualization: Unlike X-rays, MRI uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves (not ionizing radiation) to generate highly detailed, cross-sectional views. This allows neurosurgeons and radiologists to visualize the spinal cord with exquisite clarity, including:

- The Split (Hemicords): Confirming the presence and exact location of the partial or complete splitting of the spinal cord into two hemicords.

- The Dividing Septum: Characterizing the nature of the septum that causes the split, whether it is fibrous, cartilaginous, or bony. This distinction is crucial for surgical planning.

- Degree of Tethering: Precisely determining the level of the conus medullaris and the extent to which the spinal cord is tethered (fixed, stretched, or abnormally low) by the septum or other associated structures (e.g., a thickened filum terminale).

- Associated Pathologies: MRI can also identify other common abnormalities often accompanying Diastematomyelia, such as a syrinx (a fluid-filled cavity within the spinal cord), an intraspinal lipoma (a fatty tumor), or a dermal sinus tract (a small channel connecting the skin surface to deeper spinal structures).

- Essential for Surgical Planning: The detailed anatomical information provided by MRI is absolutely essential not only for confirming the diagnosis but, more importantly, for meticulous surgical planning. It allows the surgical team to map out the precise anatomy of the defect, identify critical neural structures, and strategize the safest and most effective approach for septum removal and cord untethering. Multi-planar views (sagittal, axial, coronal) provide a complete 3D understanding of the complex anatomy.

4. Additional Tests: Refining the Picture and Assessing Function